This is my in depth look into why the community grid should be approved by New York State to replace the current I-81 viaduct. The following piece was written before the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) was released in mid-April 2019 in regards to the I-81 project. Although some of the numbers from the previously leaked report are now out of date, they remain useful for the analysis and would still hold true with the new numbers.

I hope this helps to inform the discussion as we now move forward into the comment period for the DEIS. Although the community grid is the preferred option, that does not mean it will be selected in the end. It also means that we must advocate for further inclusions to the plan, which I lay out a few at the end. As always, I love to hear what people are thinking on these subjects and invite a discussion.

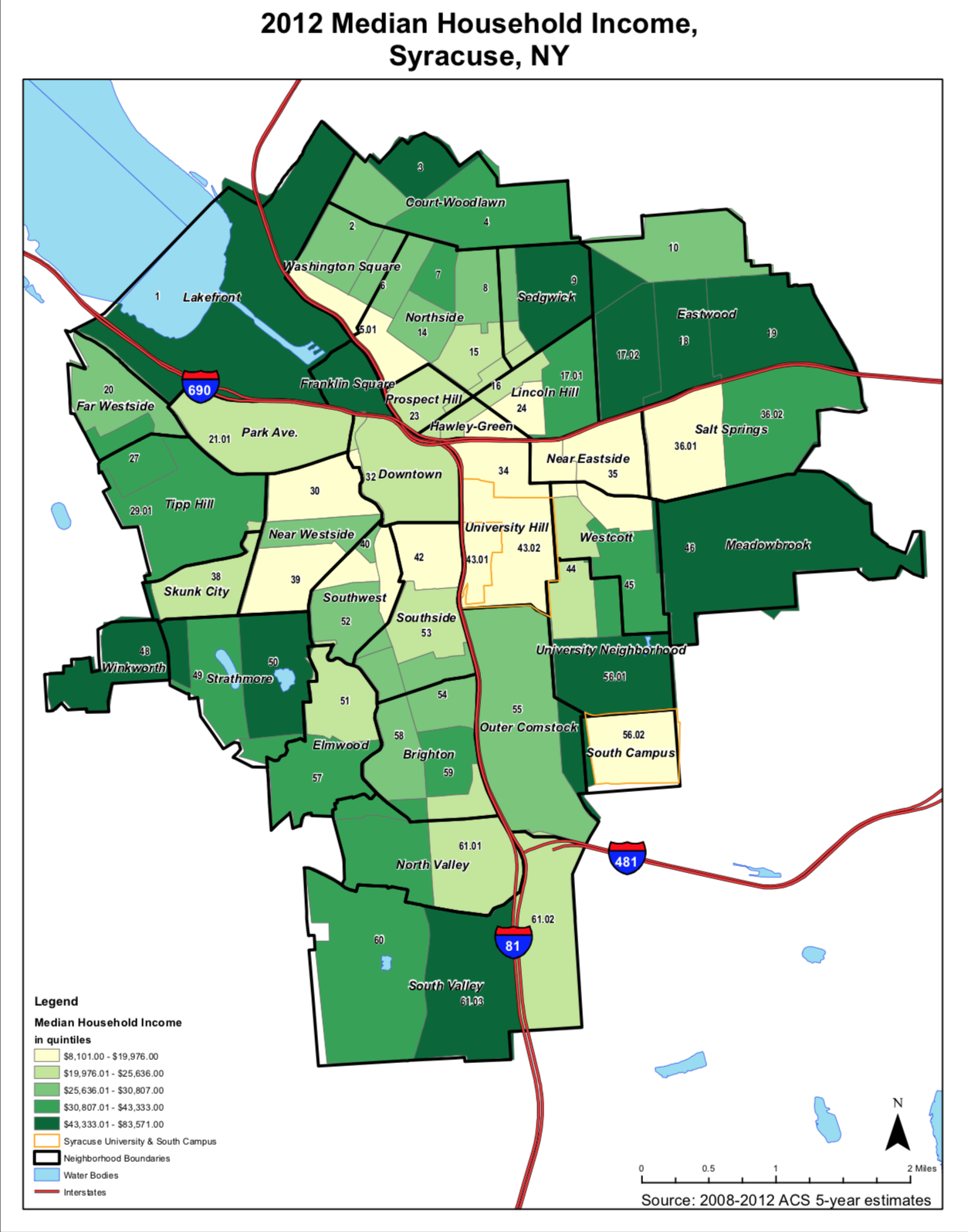

The Syracuse metropolitan area has some of the highest concentrations of poverty in the United States for African Americans and Hispanics, along with dramatic racial and economic divides between the city and its surrounding suburbs. The current footprint of I-81 has furthered this divide within the community. The decision on how to replace the aging viaduct must be made with economic and social equality in mind. To address these issues, the following memo will provide: a brief summary of the socioeconomic breakdown of the Syracuse region; an understanding of the impacts I-81 has had on furthering the socioeconomic divide within the community; and, a review of the current options for replacing the I-81 viaduct (a new viaduct, a community grid, or a tunnel), including the concerns raised by the community for each option.

Based on the analysis, I recommend the New York State Department of Transportation opts to pursue the Community Grid option with added emphasis on:

Enhancing public transportation with bus rapid transit (BRT)

Returning newly uncovered lands to the city

Some to be sold for private development

Some developed into low- and medium-income housing

Connecting residents of public housing with work opportunities on the project

Background on the Syracuse Metropolitan Area

Syracuse is the fifth largest city in New York State with a population of 144,405 and sits within a metropolitan statistical area (MSA) of 659,262 (U.S. Census Bureau). Our MSA consists of three counties; Madison, Onondaga, and Oswego. In order to gain a fuller picture of the region you must also include Cayuga, Cortland and Oneida counties as they’re economies are tied closely to that of Syracuse, which pushes the region’s population to 1,018,239 (U.S. Census Bureau).

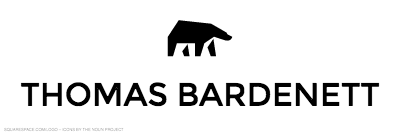

We must look at the counties outside of Onondaga County due to the commutes required into the Syracuse area. Each county has a relative high percentage of residents working outside their home county, with the main employment destination being near Downtown Syracuse (see employment maps below). With residents being primarily dependent on personal vehicles, the interstate network in the region is vital to their transportation needs (see Public Transit Usage in Table 1). Those traveling from east or west will be most likely to utilize I-90 and I-690 in order to access the downtown area. Oswego County, coming from the north, will utilize I-81 until the I-690 interchange in Downtown Syracuse. Finally, Cortland County residents, coming from the south, are the most likely residents to use the section of the I-81 viaduct in question for replacement; namely the 1.4 mile section from the southern I-481 interchange up to the I-690 interchange in Downtown Syracuse.

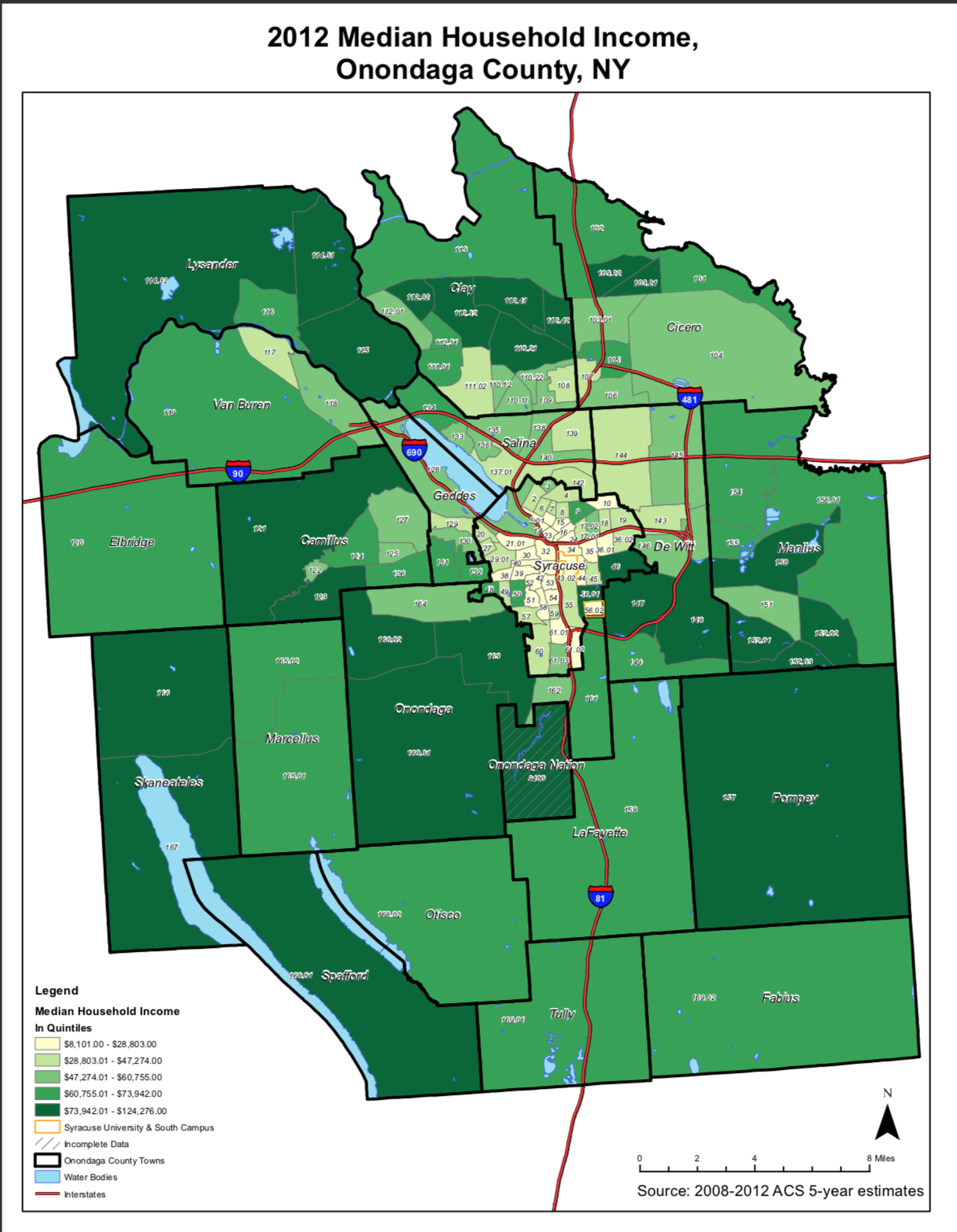

Within Onondaga County we must also acknowledge the dominance of traveling by personal vehicles and the continued reliance on the interstate for commutes. Again, the towns in the southern portion of the county (Fabius, Lafayette, Marcellus, Otisco, Pompey, Skaneateles, Spafford, and Tully) are the most likely to use the portion of the I-81 viaduct in question.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates

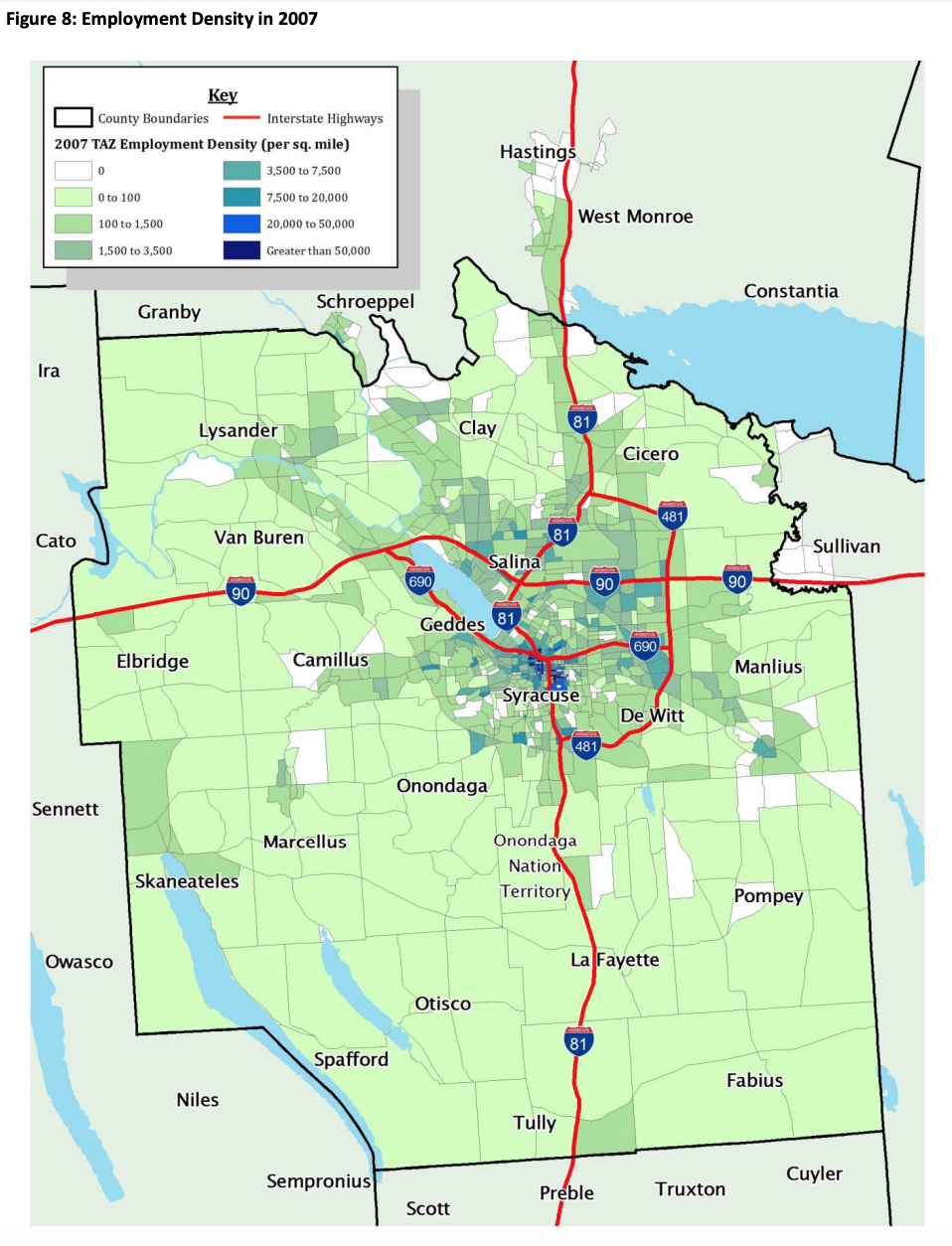

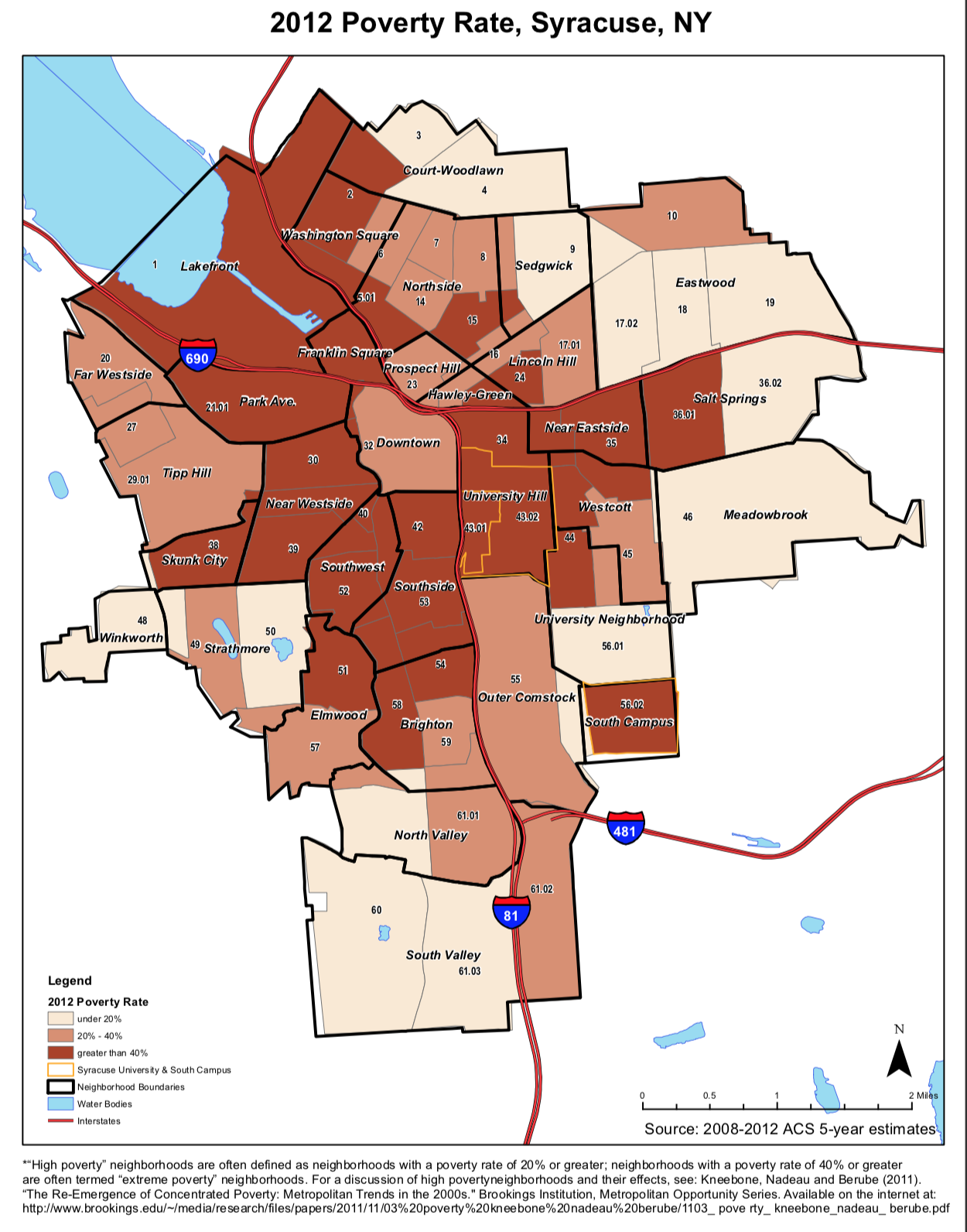

These counties and towns are significantly less diverse racially and economically compared to the City of Syracuse. This diversity is important to consider due to the history of I-81’s current footprint, which resulted in the destruction of a majority African American neighborhood (Haas). As of 2017, the census tracts located directly adjacent to I-81 are predominantly Black or African American with poverty concentrations of up to 63% (U.S. Census Bureau). Onondaga County as a whole is predominantly white with relatively low levels of poverty (see maps below), as are the surrounding counties.

The I-81 Viaduct

With the I-81 viaduct having reached the end of its useful life in 2017, we must consider the alternatives with respect to the socioeconomic differences within the region to find the solution that best promotes equity amongst residents. The three current options include:

Rebuild the viaduct up to modern federal DOT standards ($1.7 billion)

Replace the highway with an improved street grid while sending through traffic along I-481 outside the city; known as the community grid ($1.3 billion)

Build a tunnel through the city with elements of the community grid plan on top of the tunnel footprint; known as the hybrid option ($3.6 billion) (Hannagan).

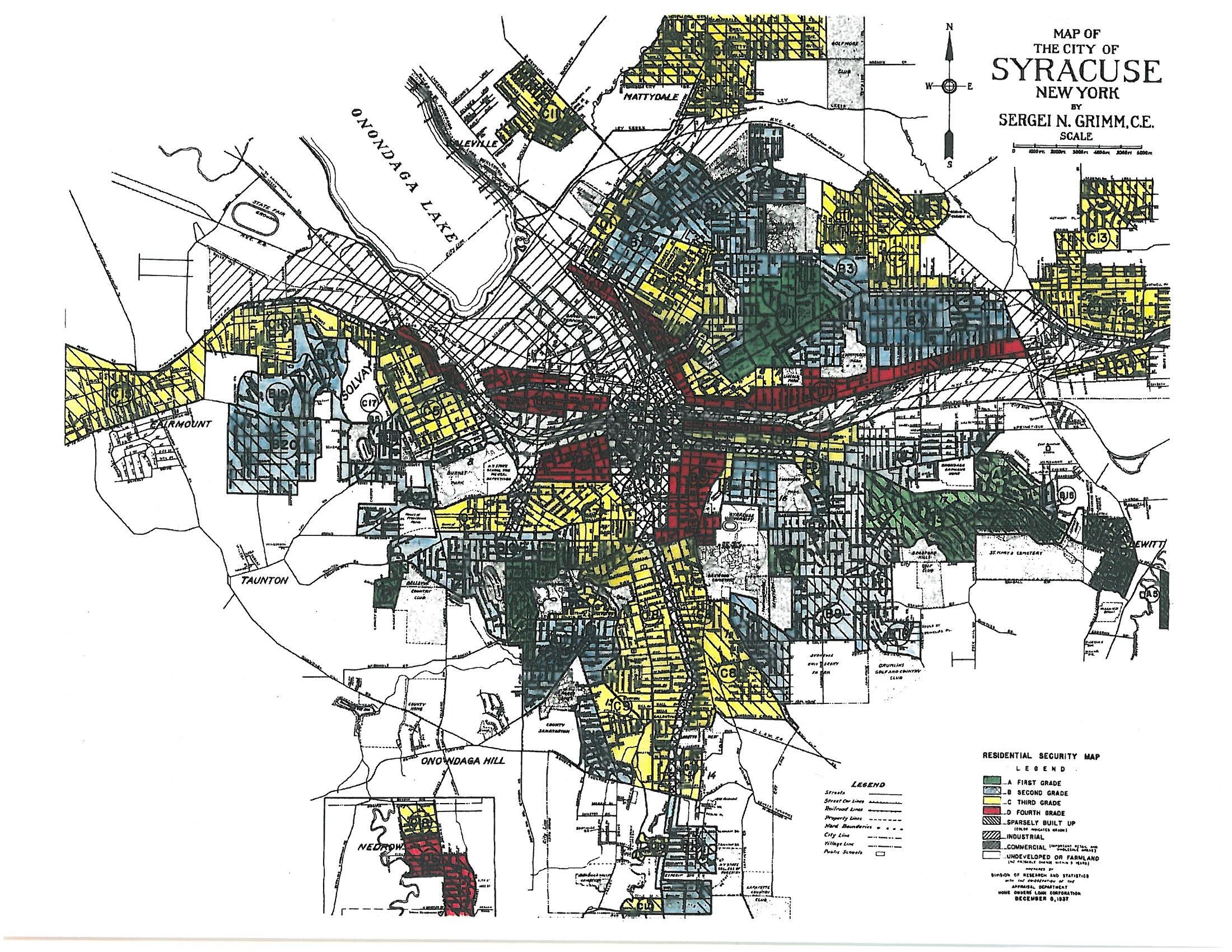

The 1.4 mile section of the viaduct in question runs from the southern edge of Syracuse north until the I-690 interchange. To the east of the highway is Syracuse University and SUNY Upstate Medical Campus, two of the largest employers in Central New York. To the west of the highway resides a mixture of low-income and public housing that reach to the edge of Downtown Syracuse. The viaduct’s footprint runs directly through the former 15th Ward, a predominantly African American neighborhood that was deemed uninsurable for federally backed mortgages during red lining (see Red Lining map below).

Syracuse Red Lining Map from 1937

During the original planning for I-81, African American residents found themselves segregated to the 15th Ward, with many realtors refusing to show suburban houses to them. This resulted in a neighborhood that was three times as dense as the rest of the city, including numerous buildings falling below safety codes. The state saw the interstate system as a form of slum clearance and a way to bolster housing demand (Haas). The mayor at the time, Anthony Henninger, believed that the highway would box in the downtown area and strangle the growth of the city (Croyle). Many others believed the growth of the suburbs would help propel growth in Syracuse as well. Instead, many businesses along South Salina St. have closed, or were torn down to be replaced by gas stations, while the suburbs have continued to expand. Housing options were limited for African Americans, resulting in many being forced into newly constructed public housing (Haas). In this way, I-81 has always had unequal effects on the community depending on who you are and where you are from.

While the bulk of the construction will be centered in the City of Syracuse, the effects of the chosen plan will be felt throughout the region, just as the original plan was. On that note, there are a few major concerns that residents and elected officials have raised.

Access to Community Resources

The first concern to many residents is how each proposal will affect their accessibility. Syracuse has relatively short commute times compared to most of the country. Many suburban residents are concerned that their commutes will be drastically longer should the community grid option be chosen. Documents released from a preliminary Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) from 2016 show most commutes would be more or less unchanged when comparing the community grid to current conditions (New York State Department of Transportation. “Alternatives.”).

For those living in Dewitt along I-481, there has been concern about the increased usage of the route as thru-traffic would be rerouted around Syracuse, including truck routes (Magnarelli). As part of the mitigation plans, I-481 would see improvements that would likely include sound barriers, to counteract any increase in traffic.

Hotel owners just north of Syracuse are concerned about the loss of business due to the removal of the highway, noting that 20% of their guests do not have reservations when they arrive (Lohmann, “I-81 Voices…”). In his town hall on the subject, Representative John Katko (R-Camillus) reassured the hotel owners that they would still be located off of I-90, which would still bring in travelers.

One group, Save 81, has focused on proving that the community grid cannot support the traffic that heads into Syracuse each day. They have warned that over 100 intersections would see their level of service drop a full level, including 61 that would rank as an E or F (Lohmann, “I-81 Grid Opponents…”). While these concerns are valid, most level drops will be negligible. In Syracuse, most roads are rated with very high levels of service, A’s or B’s. Dropping from an A to a B would go unnoticed by most drivers (Lohmann, “I-81 Grid Opponents…”).

On the other hand, the current viaduct and its replacement do not provide adequate access for the communities directly beside it. While many will argue that residents can walk underneath the viaduct to reach employment opportunities on the other side, the street network below the viaduct is dark, cluttered, and unfriendly to pedestrians. A revamped viaduct would be taller, allowing for more sunlight to reach beneath it, but would not solve the problem of high traffic volumes funneling towards the on-ramps.

Source: I-81 Independent Feasibility Study November 2017 by WSP

The Orange tunnel option, the preferred tunnel path, would seem to appease both residents needing improved pedestrian access and suburban commuters concerned about having high speed access through the city. Ultimately, the plan would not provide any exits from when it initially goes underground until it reemerges at the I-690 interchange (see map above). This configuration would result in a large portion of the commuter traffic to opt for the street grid to reach their destinations, removing any benefit of high speed travel for commuters.

Safety

Along with accessibility, many worry about the safety of their communities. The preliminary DEIS produced estimates on different types of vehicular accidents at peak hours to compare the effectiveness of their safety measures (see Table 2). The preliminary DEIS did not compared any of the tunnel options due to the plans being deemed inappropriate for the scope of this project. The results show dramatically lower accident totals for the community grid when compared to the current highway and the new viaduct design. This is mostly attributed to slower speeds and the street design.

Source: New York State Department of Transportation. I-81 Viaduct Project: Draft Environmental Impact Statement and Draft Section 4(F) Evaluation (Preliminary)

Safety goes beyond vehicle accidents. Neighbors who live directly beside the highway are exposed to high levels of toxins from exhaust fumes that often lead to persistent asthma in children. While these cases have seen a decrease over the last two decades, most likely due to improved fuel efficiency and increased regulations, there is still a strong link between living beside highways and asthma rates (Khreis). Researchers have shown that poorly controlled asthma can lead to more frequent absences in school and lower grades overall. Many of these students live in poor neighborhoods without access to healthcare that can help prevent chronic asthma (Preidt).

Neighbors in Dewitt along I-481 are right to be concerned with the emissions from increased traffic but their neighborhoods are more sparsely populated and are at an increased distance from the highway (see maps below). I-81 currently sits directly above some of the most impoverished neighborhoods in the region, resulting in their children underperforming in school due to absences and health issues, creating a cycle that goes unbroken.

The tunnel option, while removing cars from the surface, will continue to release exhaust fumes into these same low-income neighborhoods through its ventilation system. To maintain clean air within the tunnel, large ventilation plants would need to be constructed to pump out the exhaust. These plants are often placed in low-income neighborhoods and placed without concern for how they visually impact their surroundings (“Vent Buildings…”).

Taxable Property/ Economic Impact

Syracuse, like many central cities, struggles with an abundance of tax-exempt land. Over half of the land in the city is off of the tax rolls; including Syracuse University, SUNY Upstate Medical Campus, churches, government buildings, parkland, etc. (Lohmann, “If ‘Community Grid’ Replaces...”). As we know from research from Dreier, et al (“What Can Motown…”), central cities have felt an increasing burden to provide services from federal and state mandates without financial support. With property taxes as one of the only financial levers city governments have to raise funds, this abundance of tax exempt lots creates an added stress to an already financially strapped city.

City residents are rightfully concerned with the retention of tax paying properties through this reconstruction project. Rebuilding the viaduct up to current DOT standards would result in a wider, taller structure with a straighter course. This new path would require the destruction of 24 buildings, including some historic structures. The community grid and the tunnel would require far fewer demolitions; five and twelve, respectively (Hannagan).

On top of preserving structures, the community grid and the tunnel, to a lesser extent, will open up land for development. If the community grid is chosen, the removal of the viaduct will free up over 18 acres of land. This land could generate up to $33 million in tax revenue every year for the city (Lohmann, “If ‘Community Grid’ Replaces...”). The tunnel would allow for slightly less development due to the structure of the tunnel preventing construction of supports for buildings on the surface (WSP), but ultimately would create room for new development.

While the tunnel offers opportunities for new development, the benefits are offset by the estimated $10 million in maintenance costs per year. This includes running pumps to remove salt water and around the clock monitoring (Lohmann, “I-81 Tunnel…”). Some have offered up the idea of paying tolls to use the tunnel, but that would likely reduce usage to a point where the high speed access is unnecessary (Lohmann, “I-81 Voices…”).

Recommendations

Based on the information provided, I must recommend that the New York State Department of Transportation move forward with the community grid option. The current viaduct, and any other future high speed route through the city, acts as a physical barrier to marginalized communities directly adjacent to its path. The community grid offers an opportunity to remove the barrier, improve pedestrian and public transit connections to the neighborhood, and encourage private investment on the newly usable land. Beyond choosing the community grid, there are three specific policies that must be in place to ensure that the growth spurred by this development is equally shared.

Enhance Public Transit/ Implement Bus Rapid Transit (BRT)

With large percentages of residents adjacent to the viaduct having no access to a private vehicle, providing improved public transit service is vital to increasing accessibility. While residents live within close proximity to a high concentration of employment opportunities, many require advanced education and skills. Low-skill work has moved outside of the city, requiring longer commutes for residents and prompting some employers to overlook city residents for these opportunities (“Ending Spatial…”). This is a trend that researchers have noticed time and again; applicants being characterized due to the address on their application, not based on their skills and knowledge (Squires, 53-53).

As part of the funding for the community grid, there should be additional funding put in place to expand bus service as well as develop BRT routes through the city. The Syracuse Metropolitan Transportation Council (SMTC) has already developed plans for two BRT routes through the city, connecting many low income neighborhoods with employment and education centers. The plan would cost $30 million to build out and $8 million a year to run the service (Abbott). This funding is more than CENTRO, the local transit authority, is able to come up with on its own, but is a fraction of the price difference between the community grid and a rebuilt viaduct. Funding BRT through Syracuse would help improve accessibility for the least mobile residents in the region.

Return Uncovered Land to the City/ Build Affordable Housing

As previously mentioned, the community grid would free up over 18 acres of land for redevelopment. Due to this project being conducted by the state, the land would still be under state ownership when the viaduct is removed. It is within New York DOT standard practices to return all land not needed for future transportation purposes back to the city (Lohmann, “If ‘Community Grid’ Replaces...”). The city should first look for opportunities to build affordable housing on the newly acquired land.

This construction should be tied to the Blueprint 15 plan to rebuild affordable and mixed-income housing on the current sites of Pioneer Homes, McKinney Manor, and Central Village. These public housing communities are the oldest in New York State and offer substandard living conditions for residents. The Blueprint 15 plan calls for the demolition and reconstruction of the entire neighborhood with an aim of mixing low-income housing with attracting private commercial development (Eisenstadt). The city should require that the newly uncovered land be used as the beginning of this development. Building housing on the new land first and giving priority to public housing residents before beginning the demolition of the old structures. Mixed in with the new low-income housing should be private development that will help bolster the city’s tax base. This land should not go to the universities in the area, but instead tax-paying developers that are willing to commit to providing affordable housing.

Connect Residents with Employment Spurred by Construction

The final piece is the requirement that residents located adjacent to the viaduct should be in line for employment on this project. This may require an apprenticeship program for construction workers, training for positions as a bus operator, or maintenance positions on the newly constructed housing units. Without an employment guarantee for local residents, they will not be able to fully share in the economic stimulus that comes with a project of this size. Teaching residents the skills necessary to participate in the project will also provide them opportunities long after the construction is complete. We must look to use state funding to improve the lives of citizens beyond a single infrastructure project.

The proposed Community Grid design

Works Cited/ Bibliography

Abbott, Ellen. “Could 'Bus Rapid Transit' change the way central New Yorkers get around?” WRVO, Nov. 13, 2017, https://www.wrvo.org/post/could-bus-rapid-transit-change-way-central-new-yorkers-get-around. Accessed April 26, 2019

Advanced Media NY Editorial Board. “Let’s Unite Syracuse: Replace I-81 with Community Grid.” The Post Standard, July 29, 2018, /www.syracuse.com/opinion/2018/07/lets_unite_syracuse_replace_i-81_with_a_community_grid_editorial. Accessed March 8, 2019

Centerstate CEO. Community Grid Plus: Expanding the I-81 Conversation Beyond the Highway, Feb. 22, 2019, http://www.centerstateceo.com/sites/default/files/Community%20Grid%20Plus_Web.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2019

CNY Fair Housing Council. Mapping Economic, Educational, & Housing and Neighborhood Opportunity in Onondaga County & Syracuse, NY, Prepared by Alys Mann, Alys Mann Consulting, May 2014, pp. 17, 20, 21, 31, 34, 35.

Congress of New Urbanism. “I-81: Syracuse, New York.” Freeways Without Futures, 2019, https://www.cnu.org/sites/default/files/FreewaysWithoutFutures_2019.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2019

Croyle, Jonathan. “Throwback Thursday: Editorials, Syracuse Mayor Condemn Elevated I-81 in 1958.” The Post Standard, April 13, 2017, https://www.syracuse.com/vintage/2017/04/throwback_thursday_editorials_and_mayor_warn_about_elevated_highways.html. Accessed April 22, 2019

Dreier, Peter, Mollenkopf, John, and Swanstrom, Todd. “City Limits: What Can Motown Teach Us about Wealth, Poverty, and Municipal Finance?” Place Matters: Metropolitics for the Twenty-First Century, 2014, pp. 175-191

Eisenstadt, Marnie. “$100 Million Plan Would Turn Syracuse Public Housing into Neighborhood for All.” The Post Standard, Feb. 15, 2019, https://www.syracuse.com/news/2019/02/exclusive-100-million-plan-would-turn-syracuse-public-housing-into-neighborhood-for-all.html. Accessed April 26 2019

“Ending the Spatial Mismatch in Syracuse.” In the Salt City, April 1, 2019, https://inthesalt.city/2019/04/01/endingthespatialmismatchinsyracuse/. Accessed April 26, 2019

Grimm, Sergei. Map of the City of Syracuse, New York, Dec. 1937, http://mediad.publicbroadcasting.net/p/waer/files/styles/x_large/public/201712/SWAER17121813070_0001_1.jpg. Accessed April 19, 2019

Haas, David. “I-81 Highway Robbery: The Razing of Syracuse’s 15th Ward.” Syracuse New Times, Dec. 12, 2018, www.syracusenewtimes.com/highway-robbery-5-decades-ago-syracuse-neighborhoods-were-razed-to-construct-interstate-81/. Accessed March 8, 2019

Hannagan, Charley. “Experts Share Why They Believe NY will Tear Down I-81, Put Traffic on Syracuse Streets.” The Post Standard, Oct. 27, 2016, www.syracuse.com/news/2016/10/signs_point_to_demolishing_i-81_and_putting_traffic_on_syracuse_streets. Accessed March 8, 2019

Khreis, Haneen. “Mapping Where Traffic Pollution Hurts Children Most.” City Lab, April 15, 2019, https://www.citylab.com/environment/2019/04/mapping-where-traffic-air-pollution-hurts-children-most/587170/. Accessed April 15, 2019

Lohmann, Patrick. “Grid or No Grid? See Where Groups, Politicians, Others Stand on I-81’s Future.” The Post Standard, July 29, 2018, www.syracuse.com/news/2018/07/grid_tunnel_or_rebuild_see_where_groups_officials_stand_on_i-81s_future. Accessed March 8, 2019

Lohmann, Patrick. “I-81 Grid Opponents Warn of Congestion, so Why Don’t They Release the Proof?” The Post Standard, March 13, 2019, https://www.syracuse.com/news/2019/03/i-81-grid-opponents-warn-of-congestion-so-why-dont-they-release-the-proof.html. Accessed April 21, 2019

Lohmann, Patrick. “I-81 Tunnel: Project Would Take up to $4.5 Billion, 10 Years, Long-Awaited Study Says.” The Post Standard, Dec. 4, 2017, https://www.syracuse.com/news/2017/12/long-awaited_study_i-81_tunnel_feasible_but_costly.html#incart_breaking. Accessed April 21, 2019

Lohmann, Patrick. “I-81 Voices: Truckers, Motel Owners, Suburbanites; Would You Pay a Toll for a Tunnel?” The Post Standard, Feb. 20, 2019, https://www.syracuse.com/news/2019/02/heres-four-perspectives-on-i-81-from-katkos-third-town-hall.html. Accessed April 21, 2019

Lohmann, Patrick. “If ‘Community Grid’ Replaces Interstate 81 in Syracuse, What will Happen to the Land?” The Post Standard, Nov. 12, 2018, www.syracuse.com/news/2018/11/grid_land_i-81_dot. Accessed March 8, 2019

Magnarelli, Tom. “Trucking Concerns Among Top Issues at Katko’s I-81 Town Hall in Auburn.” WRVO, Feb. 5, 2019, www.wrvo.org/post/trucking-concerns-among-top-issues-katko-s-i-81-town-hall-auburn Accessed March 8, 2019

New York Civil Liberties Union. “The I-81 Story.” NYCLU, https://www.nyclu.org/en/campaigns/i-81-story?fbclid=IwAR3fUp5vseeA6aGQk1lyW4mp3nZovNXoT-XGW-9dT2YD5E-EvUc6U2y9ruw. Accessed April 15, 2019

New York State Department of Transportation. “Alternatives.” I-81 Viaduct Project: Draft Environmental Impact Statement and Draft Section 4(F) Evaluation (Preliminary), Dec. 2016, http://graphics.advancemediany.com/2019/deis/05_Transportation_and_Engineering_Considerations_12-23-2016.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2019

New York State Department of Transportation. “Social, Economic, and Environmental Considerations.” I-81 Viaduct Project: Draft Environmental Impact Statement and Draft Section 4(F) Evaluation (Preliminary), Dec. 2016, http://graphics.advancemediany.com/2019/deis/05_Transportation_and_Engineering_Considerations_12-23-2016.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2019

New York State Department of Transportation. “Transportation and Engineering Considerations.” I-81 Viaduct Project: Draft Environmental Impact Statement and Draft Section 4(F) Evaluation (Preliminary), Dec. 2016, http://graphics.advancemediany.com/2019/deis/05_Transportation_and_Engineering_Considerations_12-23-2016.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2019

Preidt, Robert. “Poor Asthma Control Can Mean Worse Grades for Kids.” WebMD, March 11, 2019, https://www.webmd.com/asthma/news/20190311/poor-asthma-control-can-mean-worse-grades-for-kids. Accessed April 21, 2019

Squires, Gregory D. and Kubrin, Charis E. “Privileged Places: Race, Uneven Development and the Geography of Opportunity in Urban America,” Urban Studies, Vol. 42, No. 1, January 2005. Pp 47-68

Steuteville, Robert. “Time to Restore the Grid.” Public Square: A CNU Journal, April 9, 2019, https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2019/04/09/time-restore-grid?fbclid=IwAR3TlrAsSlSnprQ1cOMdQSrMOqt5tPMCmBJ3INlcADpk-2S-ypvI2QxX58I. Accessed April 15, 2019

Syracuse Metropolitan Transportation Council. SMTC Travel Demand Model, Prepared by Resource Systems Group, Inc.Version 3.023, April 2012, pp. 22, 23, 25, 26. http://thei81challenge.org/cm/ResourceFiles/resources/SMTC%20Model%20Version%203.023%20Documentation.pdf Accessed March 8, 2019

U.S. Census Bureau, 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates

“Vent Buildings Spark Controversy.” Boston.com, 2003, http://graphics.boston.com/traffic/bigdig/vents.htm. Accessed April 21, 2019

WSP. I-81 Independent Feasibility Study, November 2017, https://www.scribd.com/document/366284718/I81-Independent-Feasbility-Study-Report-Nov2017#from_embed?campaign=SkimbitLtd&ad_group=126006X1587360Xa05b94d808e88f2bed9fbf8c418f69e5&keyword=660149026&source=hp_affiliate&medium=affiliate. Accessed April 21, 2019