For the summer of 2020 I will be releasing a series of articles reflecting on some of the things cities, and urban planners specifically, can be advocating and planning for to help in our fight against the climate crisis. These pieces will reflect on our transportation networks, the need for urban living, and protecting our natural resources while bringing them into the city. While these are not comprehensive of everything that needs to be done to turn the tide of this crisis, they will provide a different vision of what our world could be like if we commit to a different form of development.

In the previous installment of this series, we looked at electric vehicles and their shortcomings in regards to addressing the climate crisis. We must recognize that breaking our cultural obsession with owning a personal vehicle is the only way to fully tackle the scale of this crisis. Instead, rethinking our public transit networks to work better with the modern form of our cities and making them fare free can help us avert the worst of what is predicted.

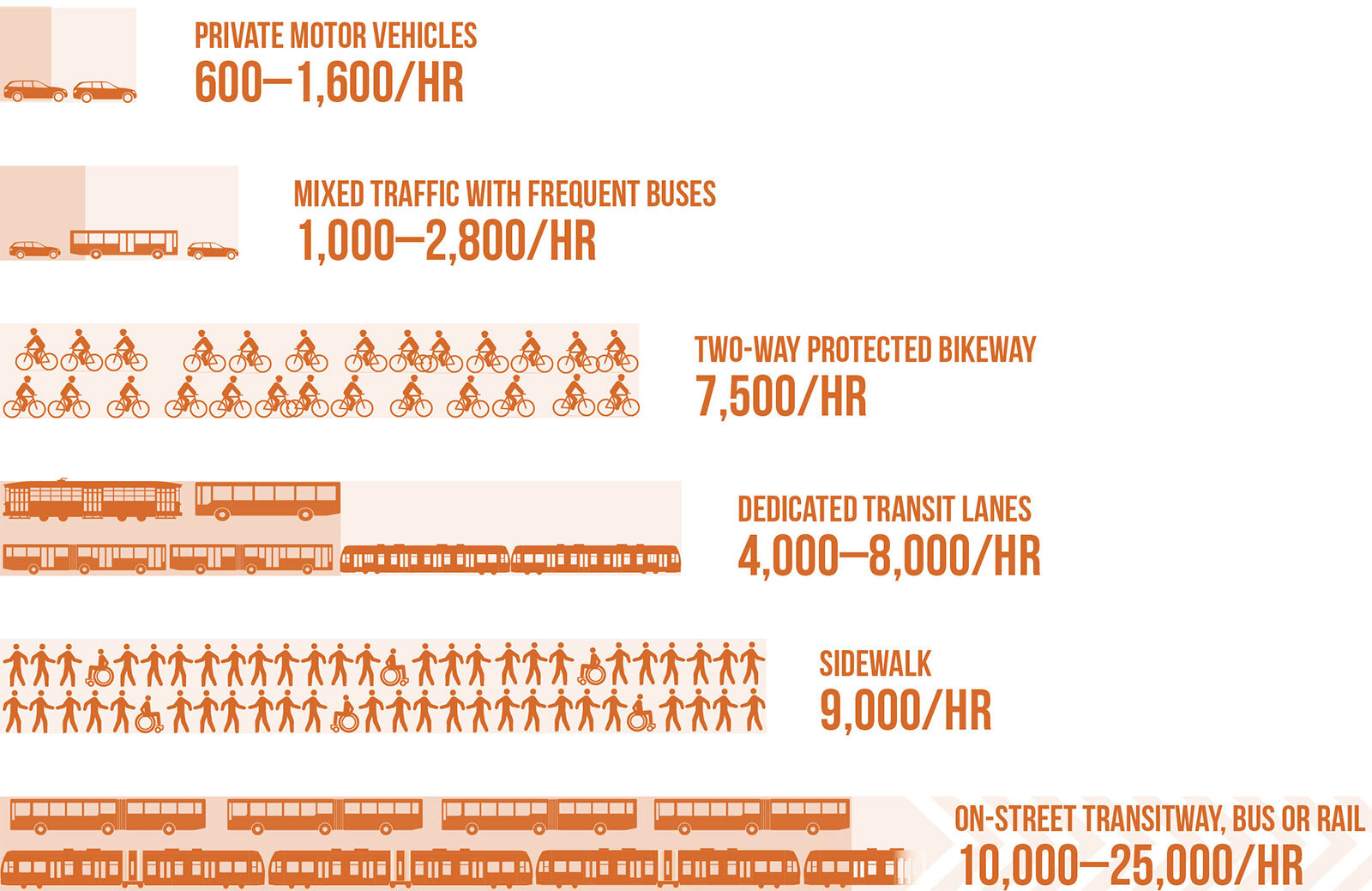

Many people will argue that autonomous vehicles will solve many of these issues and convince people to give up ownership, but we can’t wait for that technology to improve to the point where that’s even feasible. As close as we continually hear the technology is, the truth is it’s much further away as designers realize the extreme difficulty of designing a vehicle to operate in such a complex environment. Even if the technology was available and safe, the efficiency of individual cars, even if its a shared fleet, pales in comparison to a properly run public transit system, as laid out in the graphic from NACTO below.

Now imagine if we truly invested in our public transit systems and designed them in a way that fits our modern cities. Many of our transit networks have not been updated in decades, and often continue to follow the same paths streetcars laid out over 100 years ago. As you’d guess, no city is the same as it was 100 years ago; people live in different places, businesses have clustered in different patterns, and the pace of life has changed. Yet, only a small number of cities have taken on the difficult task of revamping their transit networks to reflect how their communities have evolved.

Houston, Texas is usually held up as an example of a city who took on an ambitious bus network redesign that worked, reworking their network into more of a grid with frequent connections and less of a central focus on the downtown core. But mid-size cities have also started to revamp their networks, with an understanding that their central cores are no longer the only employment centers. One local example is Rochester, NY, who’s transit provider, RTS, spent the past few years rethinking how their service will work. They did their best to balance coverage and frequency (which is the central dilemma agencies must consider, and is laid out well in the book Better Buses Better Cities), ramping up frequent service on 10 routes that serve that busiest corridors, while reimagining what service could be in the outer reaches of their service area. With an on-demand service using small vans to connect to fixed route services or, for a slightly higher price, curb-to-curb service within designated zones.

Then you can look to Albany, NY which has looked to develop some of the best bus rapid transit (BRT) lines in the country, showing that a smaller mid-size city can provide service on par with much larger cities. CDTA, Albany’s transit provider, began with the BusPlus Red Line which connects many of the region’s dense neighborhoods and employment centers, seeing ridership climb along the corridor over 20%, to nearly 4 million riders a year. Since then, CDTA has expanded BRT service along two more routes, proving that better bus service can attract riders at a much lower cost than rail service.

That’s not to say that rail service isn’t necessary in some cities, including Buffalo, NY which I’ve written about previously, but instead it's an argument in favor of cities exploring new uses for the bus first. Boston’s MBTA has been on the forefront of implementing BRT pilot programs, showing to riders and drivers alike that bus lanes and better service can help everyone. By using traffic cones to change traffic patterns to provide designated bus lanes, MBTA has improved on-time performance and sped up buses along with shortened timelines for public outreach on capital projects by demonstrating the changes being discussed while taking in real-time feedback from riders.

Improving service, primarily frequency (at least a bus every 15 minutes) and speed, will attract new riders and convince some drivers to switch modes, but in order to convince more people to take transit we must make it economically attractive as well. This comes in two ways; stop subsidizing driving and make transit free.

Our current legal and economic structures highly prioritize car usage, which has resulted in the decimation of the urban core in many cities. Parking lots have destroyed once walkable neighborhoods and have pushed residences and businesses further away from one another, resulting in people needing to drive to get to their destinations. Zonings that prioritize single family detached homes, which have a deeply racial history, are some of the main culprits for this new dispersed development pattern. The impact of our housing choices will be covered in a later installment. I also won’t focus on parking too much, but the following video from Vox and this interview with Donald Shoup in City Lab help lay out the many reasons free parking, or even the very low priced on-street parking that does exist, harms our economy and our environment.

Not only does free parking benefit those who drive, workers taking other forms of transportation rarely get free transit passes or other economic benefits for walking, biking or riding transit instead of driving. Drivers also benefit from tax breaks for buying electric cars, even though those cars still cause many of the same issues gas powered cars do. There are no tax incentives towards riding transit, even if it benefits the economy/environment more. If this doesn’t show you how much our governments have prioritized driving over all other transportation methods, consider that speed limits are set by those breaking the law. Other than the maximum (usually 65 or 70) and minimum (30 in most places, unless petitioned otherwise) limits that states set, speed limits are set by the 85th percentile rule, which incentives people to drive faster so that the speed limit gets raised.

Another major issue is the artificially low price of gas, which does not take into account its negative impacts on the environment, and the gas tax. The idea of the gas tax was originally to help cover the maintenance costs of the interstate highway system, but has failed to do so. With better gas mileage and a push towards electric vehicles, the gas tax will become even less of a funding source for maintaining roads, meaning the maintenance will have to come out of the general tax funds, forcing non drivers to pay a larger share of the costs when contributing far less to the wear and tear of the roadways. Charging people by miles traveled will help with this deficit, but should also be coupled with a plan to make transit free and get people out of their cars to begin with.

If you want people to opt into transit use you must make sure it’s frequent and easy to use. Once we change our networks to function more frequently, we then want to make it as easy to use as possible. The best way to do that is to simply make it free. Free transit may reduce costs in the long run with the elimination of fare payment systems, buses spend less time idling as passengers board wasting less energy, and no need for the policing of passengers to detect fare evaders. With most transit agencies already being subsidized to some degree, it wouldn’t cost much to cover the rest. In Central New York, to make CENTRO fare free, at its current service level, it would cost around $50 per household per year in its service counties, about as much as one fill up for a pick up truck. This fee would be much higher in cities with higher farebox recovery rates, such as NYC or Chicago, but advocating for reduced prices and congestion pricing should be able to help.

Our current transportation system will never solve the climate crisis. Unless we’re willing to make bold changes to how transit works and what transportation methods we subsidize we won’t make a meaningful difference in our fight.

4 Train at 161st Street-Yankee Stadium station in the Bronx