For the summer of 2020 I will be releasing a series of articles reflecting on some of the things cities, and urban planners specifically, can be advocating and planning for to help in our fight against the climate crisis. These pieces will reflect on our transportation networks, the need for urban living, and protecting our natural resources while bringing them into the city. While these are not comprehensive of everything that needs to be done to turn the tide of this crisis, they will provide a different vision of what our world could be like if we commit to a different form of development.

Single-family zoning found itself in the spotlight over the summer as people began to consider its racial origins through redlining practices and federal/local subsidies. Others began to turn a more critical eye towards this suburban ideal in the name of conservative economic practices, noting that the suburban experiment’s highly subsidized nature and over regulated zoning policies should upset anyone who claims to want less government interventions in private property. You can also look to the negative health effects associated with suburban living, primarily from the more sedentary lifestyle commuting requires and the increased stress levels driving produced. All of these arguments are valid and should be considered when evaluating where we choose to live, how our cities/towns choose to regulate private property, and where our tax money is sent. But we must also consider the impact our housing choices have on the environment, and perhaps living in “greener pastures” is actually the least “green” thing you can do.

First, to alleviate the concern that I’m advocating for all single family homes to disappear. Eliminating single-family only zoning would simply allow for two-family, three-family, or even four-family homes to be built in every neighborhood, along with single-family homes. Last year, Minneapolis did just that, with an eye on breaking down racial and economic barriers that have been in place for nearly a century. This has been a crucial piece needed to improve access to affordable homes across the city. Many would be surprised to know that New York City still has large areas zoned for single-family only, even amidst an affordable housing crisis. The City of Syracuse continues to perpetuate the use of single-family only zoning in their ReZone project, as many residents argue about protecting the “character of the neighborhood,” which is a common racial dog whistle. Any concern for “neighborhood character” is moot since many multi-family homes look very similar to their single-family counterparts.

Now, if we look at single-family zoning, and suburban living as a whole, from an environmental perspective the issues mostly arise from the consumption and destruction of resources. Over the last century the average American home has grown significantly in size (from around 1300 sqft. in 1960 to nearly 2700 sqft. in 2014), and many have taken up larger and larger lots. While large lot size requirements grew out of racial and economic segregationist policies, they have also resulted in pushing people further and further apart. Due to both of these factors, emissions related to travel are significantly higher in suburban areas. A report by Ed Glaeser and Matthew Kahn noted that, when controlling for family size and income, gas consumption per year per family decreases by 106 gallons when population density doubles. To showcase just how different our cities and suburbs are built, consider that Syracuse’s citywide density (5,604 people per sq. mile) is nearly five times as dense as its most populous suburb, Clay (1,216 people per sq. mile). Or, you can look at some of Syracuse’s inner ring suburbs, Geddes and Salina, where Syracuse is nearly three times as densely populated (1,813 and 2,186 people per sq. mile respectively), or more than double the density of the surrounding villages, like Baldwinsville (2,293 people per sq. mile). This emissions calculation doesn’t even take into account those who use transit, walk, or bike to get where they need to go, which would reduce the climate impact of Syracuse even further as its density and proximity to job centers/daily shopping needs allows for these alternative methods to be viable options for many trips.

Source: Bloomberg City Lab

Beyond the issues related to commuting, single family homes themselves consume far more energy than multi-family units. The chart above demonstrates the differences in energy consumption between an average suburban home, along with the multiple cars used to connect it to the wider community, and condo units located in urban centers, with fewer cars needed to complete needed trips. Even without factoring in the vehicles, or type of vehicles, the homes themselves consume significantly less energy. One of the main reasons for this difference simply comes down to size. Every year the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) constructs a dream version of the American home with the aim of setting standards for new home construction. While energy efficiency has been at the forefront of many of the newer homes, they have also grown to grotesque sizes (around 11,000 sq.ft. in 2018). While these homes are not standard by any means, they’re often used to gin up demand for many of the showcased products and styles, and, most importantly, space. This is even as the average family size has dropped by over 30 percent, resulting in fewer people occupying even more space and filling it with unnecessary purchases. You can often see this on display on HGTV with people demanding more space to host parties or have”family get togethers”, which may see that space used a handful of times per year if that, often leading these home buyers further out of the city centers adding significantly to their commutes. There’s also the effect of sharing cooling and heating amongst stacked units instead of needing to individually heat and cool multiple buildings when all of the homes in a community are detached.

The location of many of these new developments adds a third layer of harm to the environmental equation. Recent years have seen some of the worst wildfires in California history, partially amplified by the climate crisis, but also amplified due to human encroachment. As communities have sprawled outward, many have begun to live in what is known as the wildland-urban interface, the areas right at the edge of the wilderness. Not only does this increase the risk of natural disasters to the people living in these communities, but it also destroys valuable natural habitats. While many in the “back-to-the-land” movement have argued that we need to live amongst nature and move out of urban centers, the result of such movement has cost wildlife millions of acres of natural habitat and has increased rates of extinction. While we need to bring nature into our communities, ideally plant life, we should be looking to contain our own outward growth and green the spaces we already occupy.

Our current growth patterns are unsustainable in every way. Instead we should be aiming to provide more variety in our housing options and to reduce our excesses by focusing on infill projects. In most communities your only housing options are either a single-family detached home or an apartment. Some older cities still have row houses or semi-detached homes available. Condos make appearances throughout the country, but in small numbers. Part of this is due to the American obsession with home ownership, while other countries have focused on long-term leasing as a form of stability. We need to destigmatize renting and provide renters the same benefits that homeowners have in terms of tax deductions, as well as decoupling wealth accumulation from our homes. As stated previously, we need to remove single-family only zoning, along with minimum lot size restrictions, perhaps even instituting lot size maximums. We need to shift government subsidies away from suburban expansion and towards urban infill projects, rewarding developments that do not build excess amounts of car storage but instead invest in pedestrian and cycling infrastructure, or build along transit routes.

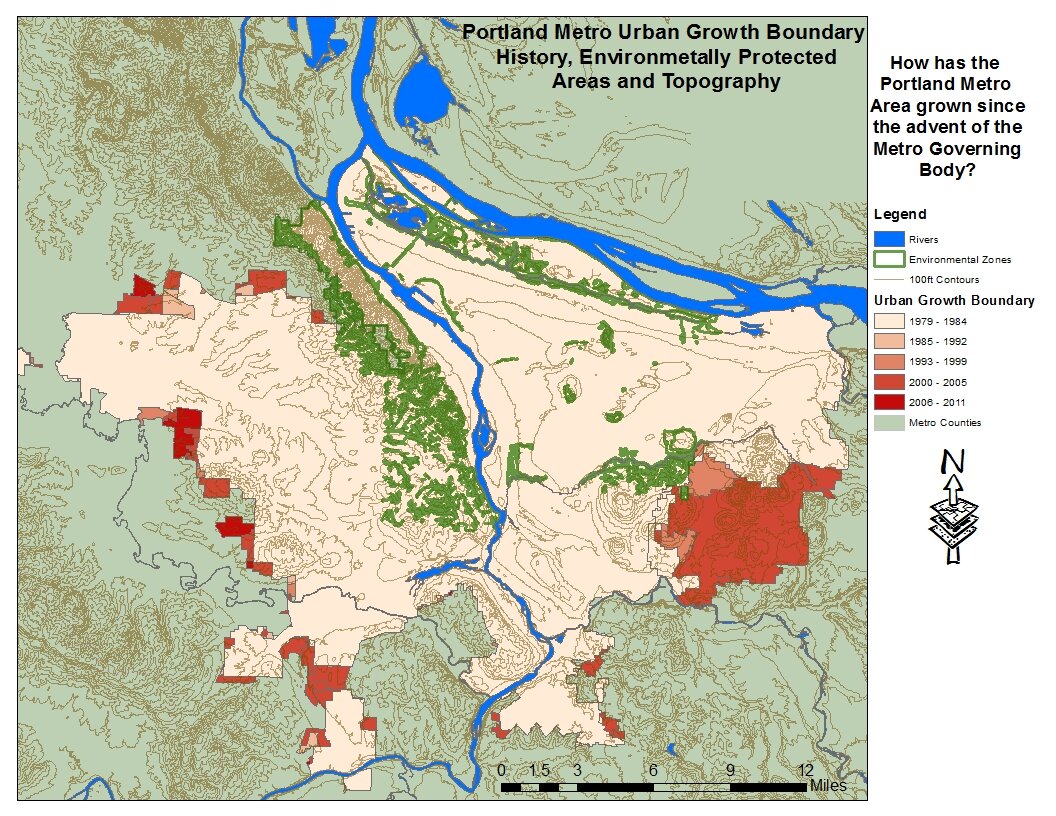

One final piece we need to embrace for this new housing to take hold is the urban growth boundary. Without restricting new construction to defined areas we will only continue to experience dangerous sprawl. Urban growth boundaries prevent greenfield development and encourage infill instead. The most famous American example of the growth boundary is in Portland, Oregon, but even that is too loose as most of the area inside the boundary is occupied by single-family only zoning and has been expanded fairly routinely. To give you an idea, Portland’s density (4,740 people per sq. mile) is still significantly less dense than that of Syracuse (yet it also has some of the highest bike ridership numbers in the country, proving that intense density is not needed for a bikeable city). Every Rust Belt city, and more importantly its metropolitan area, should have a growth boundary as populations have stagnated or declined. To have new development further away from the city without an increase in population is irresponsible environmentally and economically. It should also be significantly easier to implement in such cities, as opposed to many of the faster growing cities across the country (although it’s even more important to implement in those cities now rather than later).

When you combine all of these policies you begin to open the door to more housing at all income levels while reducing the environmental strain. When paired with the many transportation policies already discussed in this series you begin to see a more sustainable way forward with comfortably dense communities built around walking, cycling, and transit use. This is a vision that is increasingly seen as the way out of the current pandemic without doubling down on the failures of auto oriented development of the last century.