Since childhood we’ve been shown what our neighborhoods and cities could, and should, be like. Yet, we’ve continued to see our communities develop in ways that diverge greatly from these ideals. It’s time for us to look at what our childhood shows taught us about communities and how we can look to embrace these lessons moving forward. Three shows, more-so than any others, have stuck with me as I’ve grown up, and they each demonstrate the values of living in a diverse city; Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, Sesame Street, and Hey Arnold!

Life Happens Out In The Street

One of the defining features of Sesame Street, as well as Hey Arnold!, is life on the street. Characters run into neighbors and friends, immediately jumping into personal interactions they would never have had if they were stuck in a car. Sesame Street centers around the stoop of the old brownstone, with the bodega around the corner. Characters weave in and out, much like the ballet of the street that Jane Jacobs describes in “The Death and Life of Great American Cities.” When there’s a problem, someone is always around to help out. When Big Bird or Elmo want to play a game, a friend is only seconds away from passing by.

Hey Arnold! finds the neighborhood kids in the street as much as they are in school. Baseball in the back alleys, snowball fights on the main drag, and dance battles in the middle of the road. More than any other cartoon, Hey Arnold! embraced its urban setting to tell truly urban stories. Stoop Kid could never have existed out in the suburbs. The Pigeon Man needed the urban setting to look over the city and become an urban legend. Without the common space of the street, these characters would never come to interact with one another.

Public Spaces/ Informal Places

Related to life on the street is the need for public, informal spaces. Mr. Rogers often spent time in his small front yard, interacting with his neighbors. While not fully public, the space was small enough that he was part of the public sphere without being on the street. He often used the space to invite in members of the community, like the local police officer or the mail carrier. Meanwhile, Hey Arnold! thrived on these informal spaces. The kids turned a vacant lot into a baseball field, and transformed an old oak tree into an impressive tree house.

Informal public spaces allow neighbors to interact and shape their community in ways that best suit them. While traditional parks and playgrounds are vital community assets, they often come with restrictions in how they may be used. Permits may be needed to throw gatherings, or use of a field may be restricted to leagues that have rented out the space.

In many communities, kids have no way to venture out on their own within their neighborhood. Parks must be driven to so they’re stuck in their backyards with limited to no interaction with the outside world. When they do get out to spend time with other kids, it’s often through leagues or scheduled/planned events. Communities, primarily suburban communities, have robbed our neighborhoods of informality, which leads to a lack of vitality.

On the Northside of Syracuse, where my family has lived for decades, we benefitted from having a large field behind my elementary school. With chalk, a couple cones, and a soccer ball, the field would be transformed every Sunday night into a massive soccer game. Dozens of kids from the neighborhood would flock up to the park to play, never being formally organized through the city but still a reliable occurrence. This is the type of informality a neighborhood needs to thrive.

Public/ Alternative Transit Is Key

While cars may appear in each of these shows, public transit and alternative transit shows up almost every episode. Mr. Rogers welcomes a small trolley into his home each episode to take you to the Land of Make-Believe. This trolley is inspired by incline trolleys found in Pittsburgh that have helped move residents up the steep hillsides for over a century.

Sesame Street often features characters learning to ride bikes or rollerblade, and the set even features a subway stop. Each of these forms of transportation are easily accessible for kids and provide them with freedom to access the city. Hey Arnold! finds its characters on bikes or on the bus in almost every episode. They’ve grown up with a level of independence most kids don’t get to experience because they have access to transit. When kids have to be driven everywhere it limits their range of motion and decreases their independence greatly. We need to encourage kids to ride bikes, roller skate, or walk whenever possible. Sadly, many people live in communities where roads are unsafe for individuals not protected by vehicles.

Diversity!

While I have focused on the physical environment of the city so far, the most important lessons these shows taught us when it comes to community is that we should embrace diversity. Sadly, this is where our communities fail the most.

Look at the casts for each of the shows. Mr. Rogers often invited in guests of different backgrounds, whether different races, different abilities, or completely fantastic characters in the Land of Make-Believe. Sesame Street has continued to emphasize diversity in its casting decisions. Not only do human actors mix in with Muppets of various backgrounds, the human cast itself contains all different ages, races, ethnicities, and backgrounds. They often do segments introducing different languages, cultural backgrounds, and even deal with issues like homelessness. Sesame Street, more than any other show, has sought to be inclusive of everyone.

Hey Arnold! takes a more subtle approach than Sesame Street but still displays a truly diverse neighborhood that reflects the reality of urban life. Arnold’s boardinghouse alone represents a melting pot with boarders from Vietnam and Russia, some with different education levels, and others with varying upbringings. Once you start to look at the neighborhood the racial and ethnic diversity increases (Gerald and Phoebe), religious backgrounds diversify (Herald is Jewish), as do economic backgrounds (Lila’s family is impoverished while Helga comes from a generally well off family). Yet they all interact in a cohesive way that makes the neighborhood vibrant.

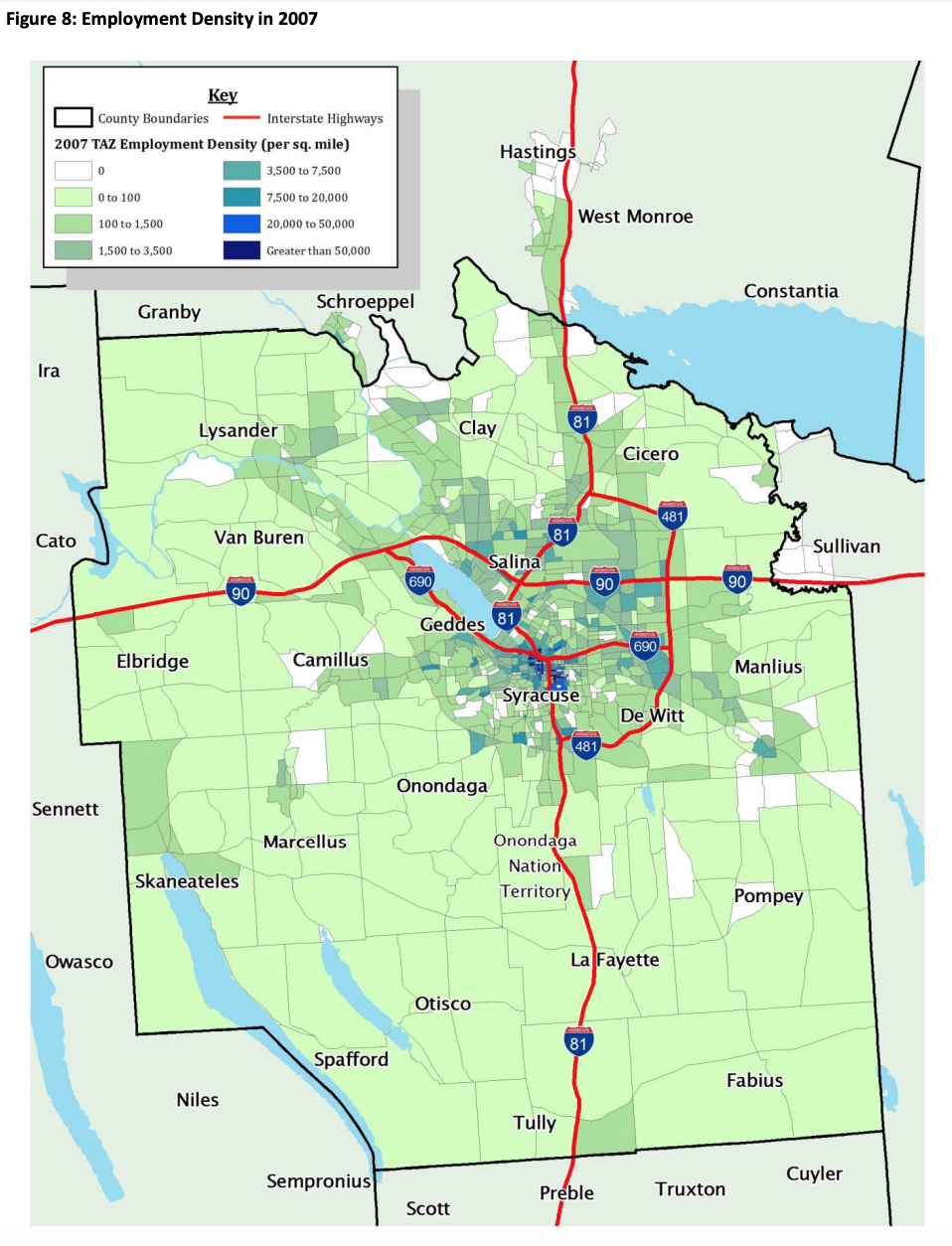

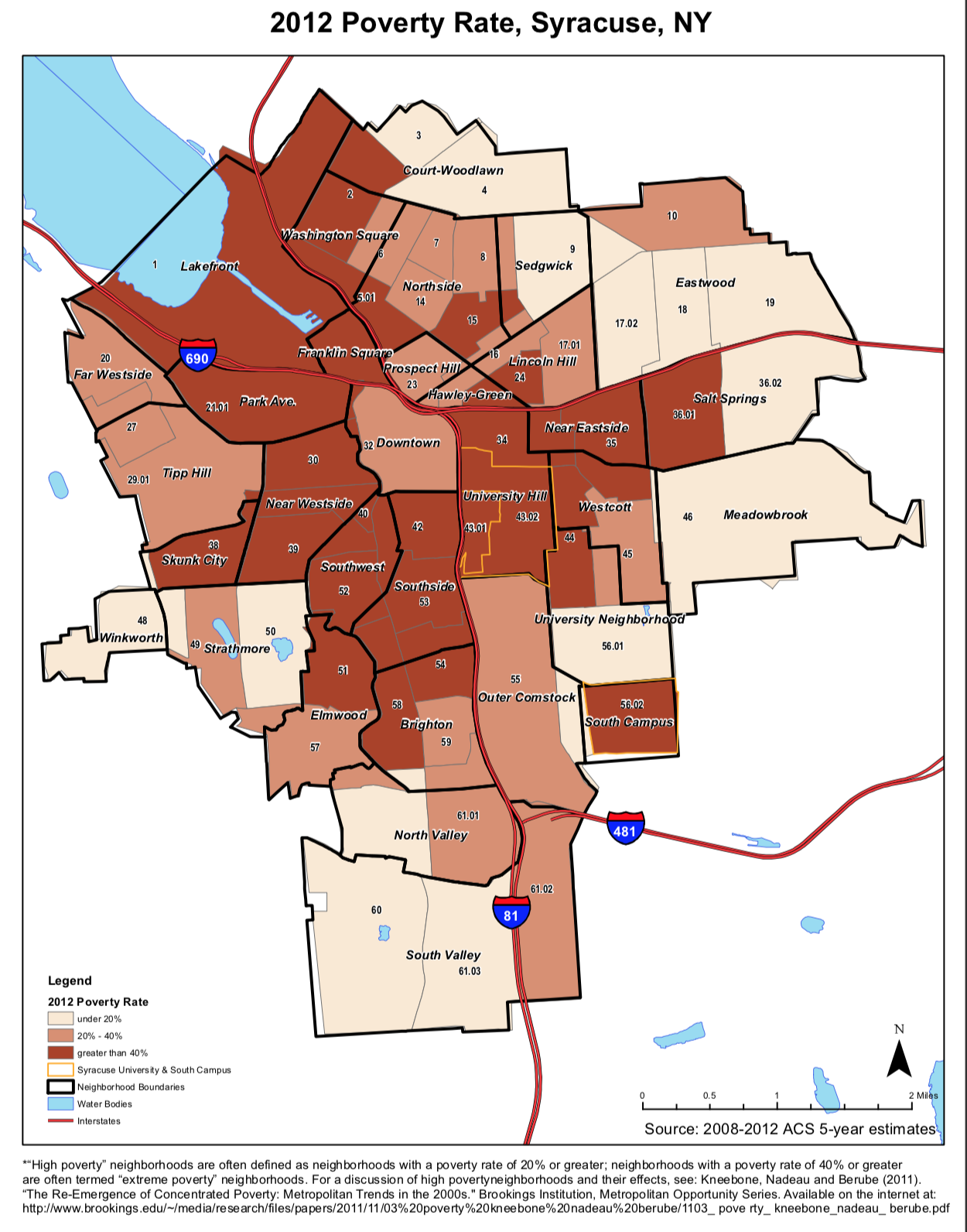

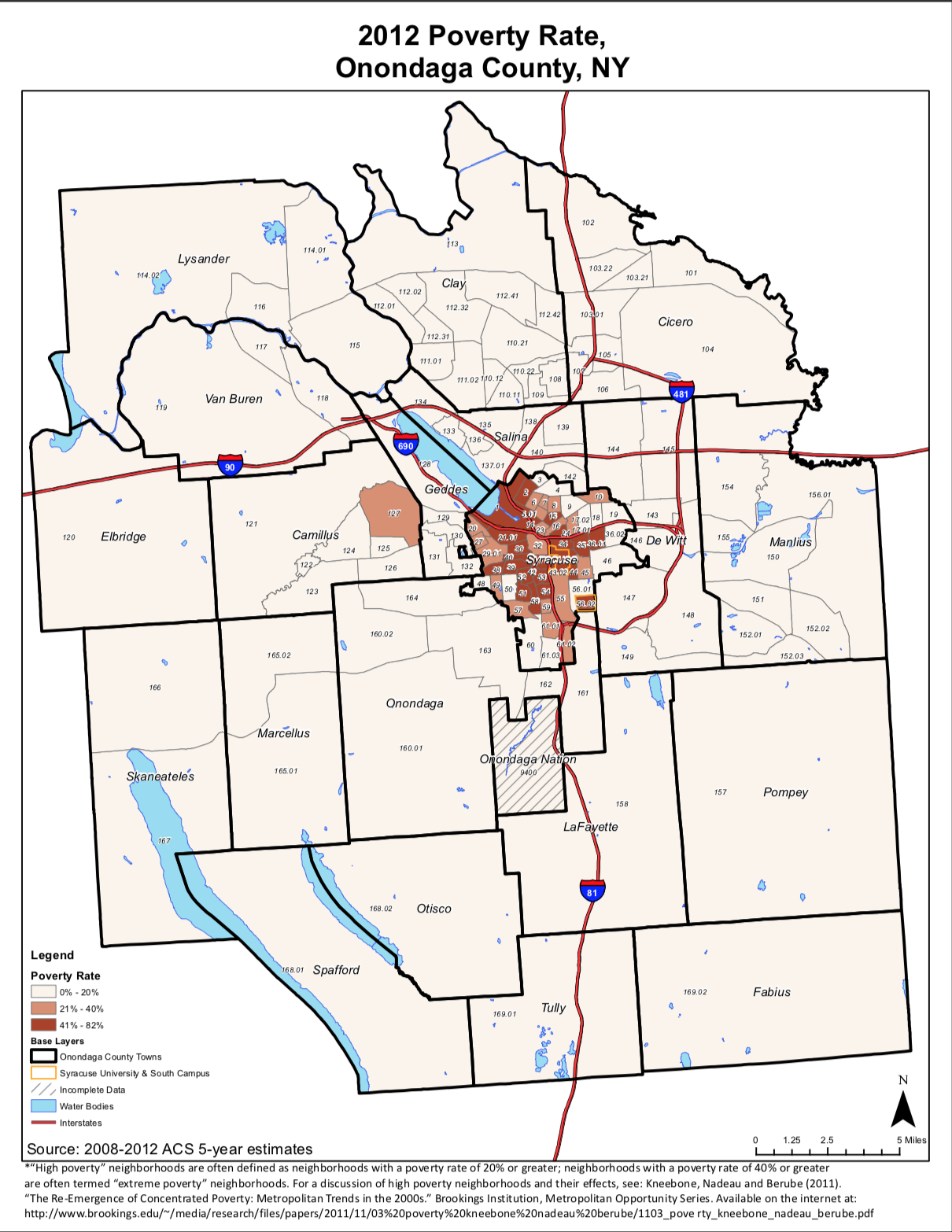

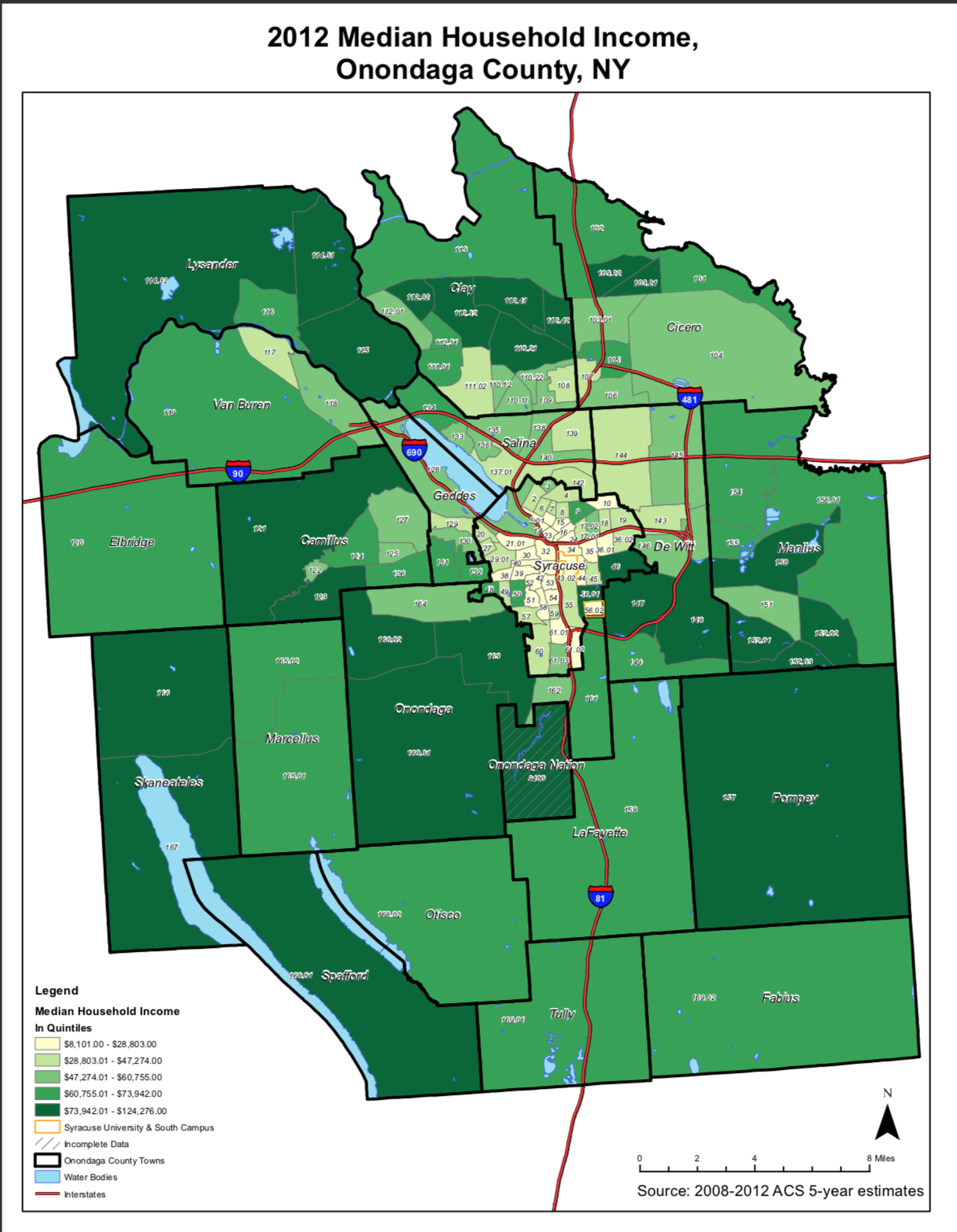

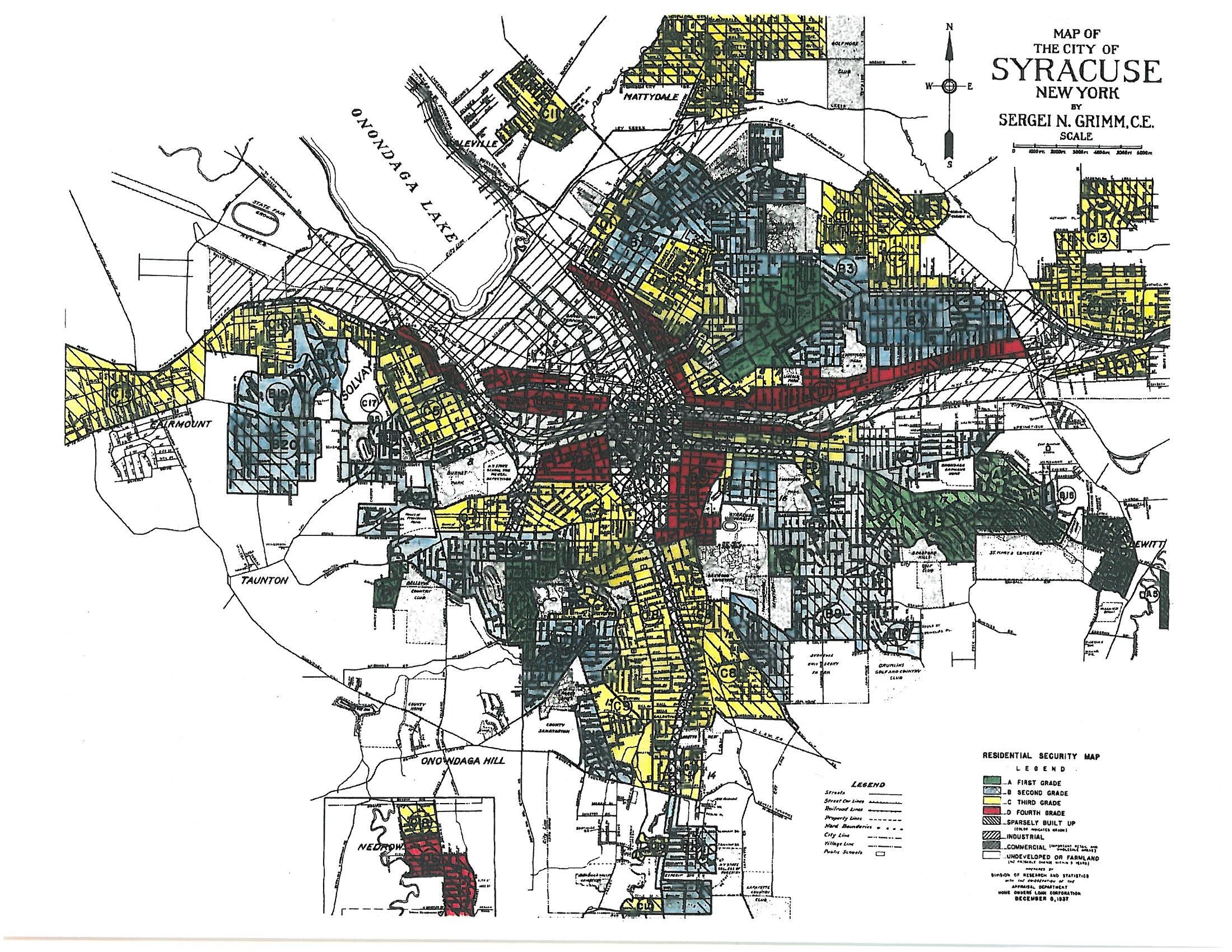

In contrast, the reality of our neighborhoods varies dramatically depending on where you live. As an example of this we can look at school district characteristics.

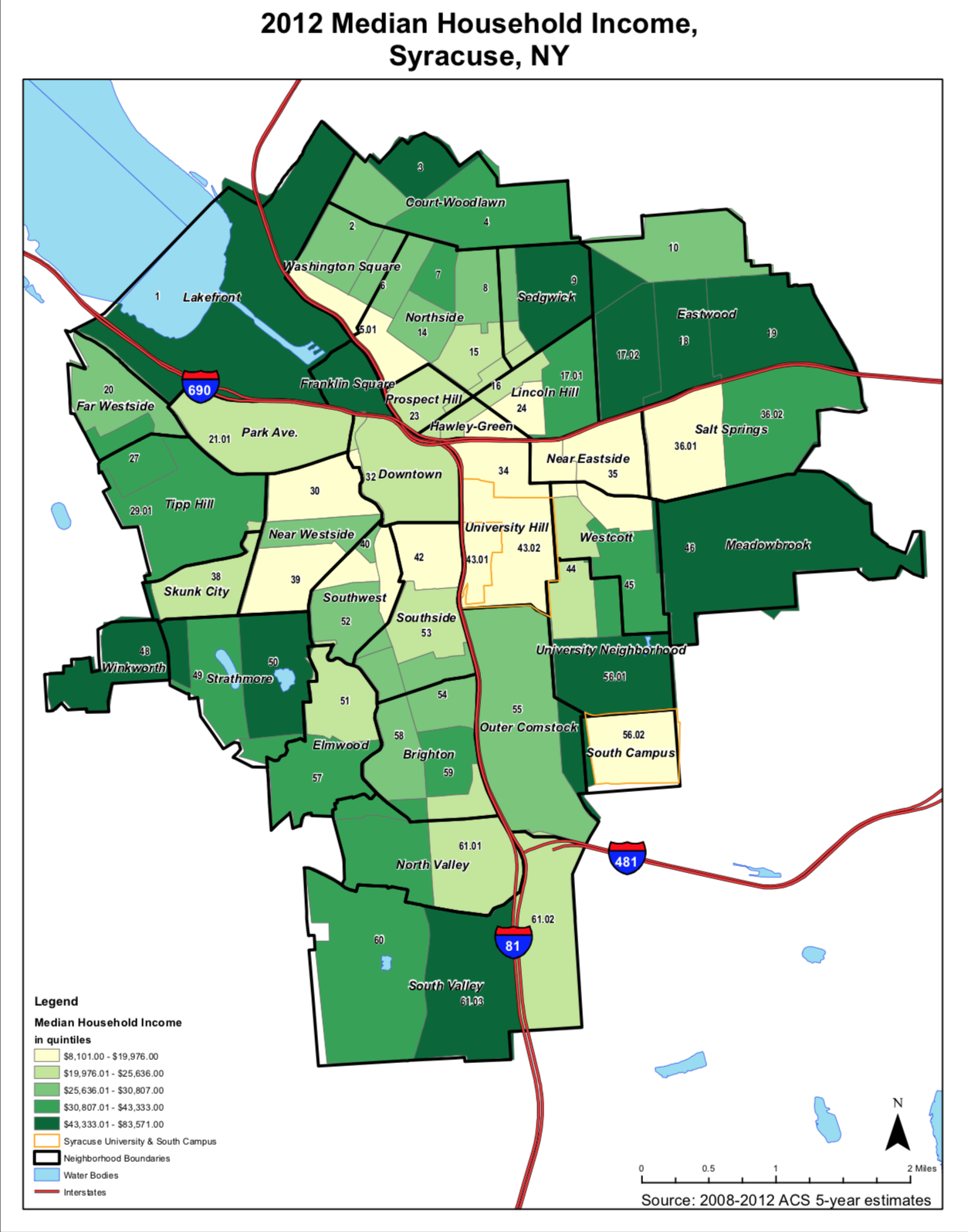

Below are two graphs that display different demographic characteristics among school districts around Syracuse, NY. One line will stand out from all other over and over again: the Syracuse City School District (Blue). Syracuse is a majority-minority district that also has high levels of English as a New Language (ENL) students, students with disabilities, and economically disadvantaged students. Why does this district stand out?

Ethnic Breakdown of School Districts around Syracuse, Ny

Source: New York State Education Department

Other Demographic Breakdowns of School Districts around Syracuse, NY

Source: New York State Education Department

Every other district is overwhelmingly white, and most are far wealthier. Yet, Syracuse must provide extra services to most of its students, services that cost a great deal more to adequately administer than the district currently has. This has also limited who is able to get services. Many students who would get extra services in suburban districts must go without in the urban district due to budget constraints. The urban district must focus on those with the most needs, which can often leave behind those with lesser, but still significant, needs.

We have failed to live in diverse neighborhoods. Many have decided to live in neighborhoods where most of their neighbors look and behave like themselves. This is not what our childhood shows taught us. We have failed to live up to the standards we were taught and it’s time that we work to change that fact.