In the time of COVID-19 we have repeatedly heard the phrase “reducing the density” as a way to combat the virus. While staying a safe distance apart from one another is important during this time, the phrasing may lead to the wrong conclusions about dense, urban development. This should not be seen as an indictment of urban living, but instead a call to arms to rethink how our cities function and who public space is meant for.

As social animals, we crave access to others, even if the way we interact and how big of a social dose we need varies. Our current urban and inner ring suburban infrastructure limits our ability to share open spaces with one another at safe distances. Newer, far flung suburban neighborhoods may have more personal open space for people to occupy privately, but they reduce the social interactions we desire with others.

It is likely that a major infrastructure bill and jobs program will materialize as a way to build back our economy. This is the moment to rethink how our urban spaces work and advocate for changes that will not only improve our day-to-day lives but also function better in times of crisis. We shouldn’t double down on the development patterns of the past, but instead look to figure out how to improve the future. In some ways, this could be the beginning of a Green New Deal that progressives have been arguing for. Here are a few ideas that we should explore:

True Neighborhood Units

Over the last several decades we’ve moved away from neighborhood businesses and schools, and we’ve emphasized distance away from others. Suburban development has been almost entirely residential with large commercial plazas attracting residents from miles away to a centralized location. Even though these plazas, which are dominated by regional and national chains, often cut the price of the distribution of goods and lower the prices of products, there are several downsides to this development style, beyond hurting small, local businesses.

As we emphasize the need to avoid close encounters with others, these centralized shopping centers make this impossible. Many communities only have one or two options for basic necessities, such as groceries, resulting in thousands of customers flocking to this single point. When a worker, or shopper, tests positive for the virus, this news now affects a wide swath of communities, making it difficult to track down how the virus may have spread. Locally, the Dewitt Wegmans, the largest Wegmans around, had an employee test positive. Figuring out who may have interacted with this employee, and then who they in turn may have infected, becomes complicated as customers spread out across the region.

A true, complete neighborhood helps simplify this process, with the added benefits of promoting locally owned businesses and a sense of community. First to define what I consider a neighborhood in this context. While most will consider a neighborhood to be related to a common history, culture, or defined by a specified boundary, but in this context I’m looking to consider a neighborhood as anywhere that you can walk to within 15-20 minutes, or up to 30 minutes in some cases. For this neighborhood to be considered complete you should be able to access grocery stores, pharmacies, small home improvement stores, along with a neighborhood bar or restaurant. A true neighborhood should provide you easy access to your daily necessities on foot.

This is how neighborhoods functioned in the past, developing close knit communities that often created distinct cultures and traditions, until we began subsidizing suburban development patterns that pushed us further and further apart. At the same time, these neighborhood units would make it easier for ourselves to isolate communities during a pandemic like we’re experiencing today and stop its spread. With most residents frequenting the stores closest to them, it becomes easier to track down customers and enforce quarantines should someone catch the disease. For communities outside of the infected area daily routine errands can continue mostly uninterrupted as long as they stay within their neighborhood unit.

Rezoning efforts that promote neighborhood business corridors and mixed-use development can spark the creation of these neighborhoods that should also be supported through tax incentives for local small businesses. Even with a new focus on localized businesses, they won’t be able to succeed if we don’t change the way people live and interact with their neighborhood.

The Return of Townhouses/ Row Houses/ Brownstones

One of the major reasons our neighborhood units began to break apart has been the emphasis on single family detached homes and the ever increasing size of the standard lot. While dense urban neighborhoods remain, they’ve become less and less common outside of major cities. Upstate New York cities have seen their populations decline and with it the population density. Even when new urban housing is built, they’re often apartments located either in the downtown neighborhoods or near local universities. Due to this, our housing options have dwindled to two primary housing types: single family detached homes or apartments. This leaves a lot to be desired, especially for people who would like to own a home but also want a more urban living style. This is why we must encourage the development of modern urban townhouses (or row houses or brownstones depending on your preferred terminology).

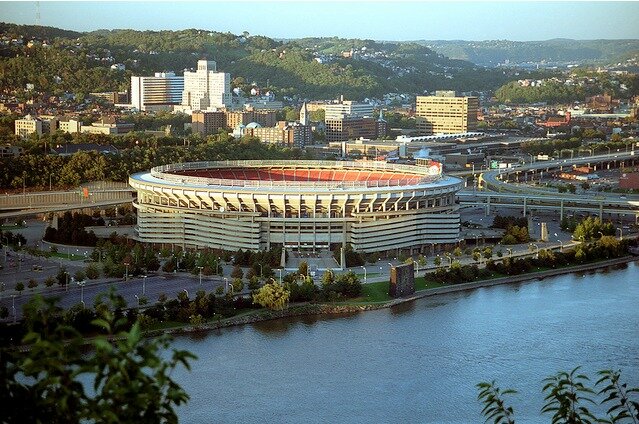

Row houses in Pittsburgh, PA. Source: PittsburghSkyline.com

Some cities have an excellent remaining stock of townhouses, with New York, Pittsburgh and Philadelphia coming to mind, but many mid-size cities no longer have a large housing stock in this style. If you’re looking for townhouses around Syracuse you’re often stuck looking in suburban developments that are poor in terms of walkability to run errands. We should be looking to correct this fact and provide opportunities for the development of urban townhouses. Right now it’s unclear whether or not townhouses are allowed under Syracuse’s zoning laws, or even the rezoning proposal. We should be more specific about how townhouses fit within our urban environment, and encourage their use near existing business corridors and proposed business corridors.

Now you may be asking why townhouses should be a part of our new urban development pattern. There are several reasons why townhouses should be an integral part of cities, but the main factor is that they provide home ownership opportunities at denser levels of development. A typical household in Syracuse has a lot around 40 ft. wide and 110 ft. deep. Townhouses typically have a lot only 25 ft. wide, allowing for nearly double the built density while still providing a decent amount of private outdoor space for residents. This increased density creates a more visually interesting and vibrant environment while still providing a significant amount of private space, but, more importantly, it makes a 15-20 minute neighborhood commute possible. At the current densities of most neighborhoods, there just isn’t enough people to provide the critical mass for businesses, other than corner stores, to survive from local commerce only.

As these densities increase, along with the amount of local commerce, we must ensure that there is plenty of space for residents to spread out and engage with their communities, even in times where social distancing is required.

A Network of Bike Boulevards and Mixed-Use Paths

One of the few promising developments happening during this pandemic is the new emphasis on expanding public spaces for people on foot. New York City has started a pilot program shutting down a number of blocks along Park Ave. so that residents can get out and walk while keeping extra space between one another. This builds off of the success of the 14th Street Busway also in NYC, and the Market Street Busway in San Francisco. We’re starting to see leaders acknowledge that we have plenty of public spaces within our cities, but we’ve given over too much of it to cars.

Communities across the country are seeing an increase in the number of people walking around their community as a way to get out and get fresh air during this time, but many do not have safe spaces to do so. An article out of Cleveland noted that many suburban residents were heading into inner ring suburbs or the city to walk on sidewalks since their own communities don’t have any. A Guardian article notes that joggers and walkers are now competing for a finite amount of space available on a sidewalk. We can even look in our own communities where our neighborhood sidewalks are often, at their widest, maybe 5 ft. wide, making it difficult to walk next to someone and completely impossible to keep proper distance away from one another during this time where 6 ft. is considered the minimum. In more usual times, these sidewalks often discourage people from walking as they prevent us from socializing how we wish to, bring us too close to strangers, and often make us feel as though we’re invading private property even though we’re in a public space. Now that more people are looking for accessible public spaces and making use of our current infrastructure, there may be a new demand for better, more plentiful spaces.

In this light we should consider remaking our neighborhood streets to emphasize pedestrians and cyclists and restrict the use of cars. This may sound crazy in a country that has been dominated by cars for almost a century, but there are many examples for us to build from. Barcelona, Spain has created a series of superblocks, routing traffic around the edges while only allowing local traffic to enter the blocks. Berlin, Germany has begun experimenting with new pedestrian malls that are essentially parks surrounded by storefronts.

We should explore creating a network of these spaces to provide plentiful amounts of open space for people to enjoy and interact with their communities, no matter the distance restrictions placed upon us. Bike boulevards, which are streets with quieting measures like speed pillows and small roundabouts, could be implemented on a small budget throughout cities to slow down traffic and provide safe spaces for people to walk and ride bikes. We may even wish to explore closing entire streets to traffic, which has already been done in Syracuse along Onondaga Creek. We should identify streets that are underused but provide helpful connections to convert into mixed-use paths that connect to bike boulevards, resulting in a vast network available to residents throughout the city.

The End Result

By combining mixed-use development, neighborhood business corridors, middle to high density housing, and more open space for pedestrians and cyclists, we can create a more sustainable city for the future, less reliant on cars and more resilient to health crises. Although I haven’t touched on public transit specifically, it should not be forgotten. Our public transit system is already vital to our economy, and should become even more integral moving forward. It’s been deemed an essential service and carries many of our essential employees to work throughout this crisis. We need to ensure that they are funded at a level worthy of an essential service.

Don’t be fooled into thinking that density is our enemy when it is in fact a solution to many of our modern problems. Countries far denser than the United States have proven that they can handle a crisis better than us; from South Korea to Singapore to Germany. It’s their policies and their sense of a common good that comes from living close to your neighbors that has helped them during the time of COVID-19. We should take time to learn from them and improve upon them to make an urban environment that truly works for people.