Baseball is often referred to as “America’s Pastime,” and a reflection of the American ideal. At the same time, few cities represent the traditional picture of American success, failure, and reinvention quite like Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Pittsburgh’s love affair with baseball, and the Pirates specifically, has lasted nearly 130 years through which the team has seen the city at the height of its industrial power, the struggles of reinvention through the Pittsburgh Renaissance, and the renewal surrounding advanced technology and education. Each era had been viewed from ballparks unique to that time. The evolving home of the Pirates encapsulates the city’s attempts at reinvention and the powerful pull of being considered a major league city.

Baseball came of age during the industrial revolution, but its roots are anchored in the rural cemetery and parks movements of the early Nineteenth Century. Increasingly dense urban centers created chaotic spaces and health concerns. Cemeteries located next to neighborhood churches were overcrowded and blamed for disease outbreaks [1]. To combat these negative aspects of early city life, cemeteries on the urban edge began to be developed in the 1830s. Mount Auburn, on the outskirts of Boston, was the first of this new wave, built where the city can still be seen but the visitor is engulfed in nature [2]. New York and Philadelphia followed close behind, with Allegheny Cemetery outside of Pittsburgh opening by 1842 [3]. Henry Bellows, in 1831, declared that rural cemeteries “are not for the dead. They are for the living [2].” Quickly these cemeteries became tourist destinations in their own right, used for carriage rides and leisurely strolls, but no active recreation was to be allowed. The distance to reach these cemeteries also came into question, leading city leaders to consider ways to provide this open space within the city itself. The parks movement sought to address these concerns by focusing on urban parks within reach of the wider masses. Central Park in New York is, perhaps, the most well known of this era with its emphasis on passive recreation and leisure. Much to the chagrin of working class individuals, active recreation and organized sports were forbidden within these parks [4]. The clamor for open space had not succeeded in providing opportunities for all people, but a park in Pittsburgh would soon combine the two desires in a unique way. In 1889, Mary Schenley would donate 300 acres of her family’s estate to the city of Pittsburgh in order to form Schenley Park in the rapidly growing Oakland neighborhood [5]. Twenty years later the park would welcome a new tenant; the Pittsburgh Pirates.

The Gilded Age, in which Schenley had made her donation, would see a diverging world within Pittsburgh, as the city would be engulfed in smoke and pollution while those who profited off of this pollution would begin a tradition of philanthropy matched by few other cities. By 1865 Pittsburgh was producing 40 percent of the iron ore in the United States. Fire and smoke from the plants filled the air. A reporter for the Atlantic Monthly in 1866 would describe the view of Pittsburgh as if “looking over into hell with the lid taken off [6].” Soon steel took the place of iron ore as the top manufacturing product of the region as Andrew Carnegie rose to prominence. Carnegie Steel, from 1888-1900, produced 30 percent of the steel in the U.S., which was equivalent to 80 percent of the entire output of England during this time [6]. Pittsburgh’s population exploded due in large part to this ever expanding industrial powerhouse that had been built. From 1870 to 1910, the city grew from 139,256 to 533,905, providing a constant flow of workers for plants [7]. Pollution from these plants was so heavy that the city was required to run street lamps during the day [8]. Yet, these industries created incredible wealth for those in charge. Andrew Carnegie would sell his steel empire to J.P. Morgan for just under $500 million, which would overwhelmingly be spent on the creation of museums, libraries, music halls, and the founding of Carnegie Tech. Over $25 million would be spent on his Pittsburgh library which anchored his investments in the Oakland neighborhood [9]. Carnegie saw his investments in the cultural center of Oakland as a way to “civilize” the common man, as he famously did not pay high wages as he felt he would spend the money more wisely. The local papers exalted Carnegie for his investments, but the working class remained skeptical of these acts. As a whole, workers became more invested in a new form of consumer driven recreational activities, namely watching a baseball game [7]. During this time, the Pittsburgh Pirates had been playing at Exhibition Park, a rundown ballpark on the banks of the Allegheny River, which flooded often. While upper class patrons attended games along with their working class counterparts, women were a rare site as they were not fond of its Northside neighborhood. Barney Dreyfuss, the owner of the Pirates, knew that baseball could become a higher class institution and sought the help of Franklin Nicola, a real estate agent in Oakland. Dreyfuss recognized the important developments happening within Oakland at the hand of Carnegie and wanted the Pirates to become part of this new cultural center. Through Nicola, Dreyfuss and Carnegie worked together to purchase a seven acre piece of Schenley Park, bringing the Pirates closer to their new home [5].

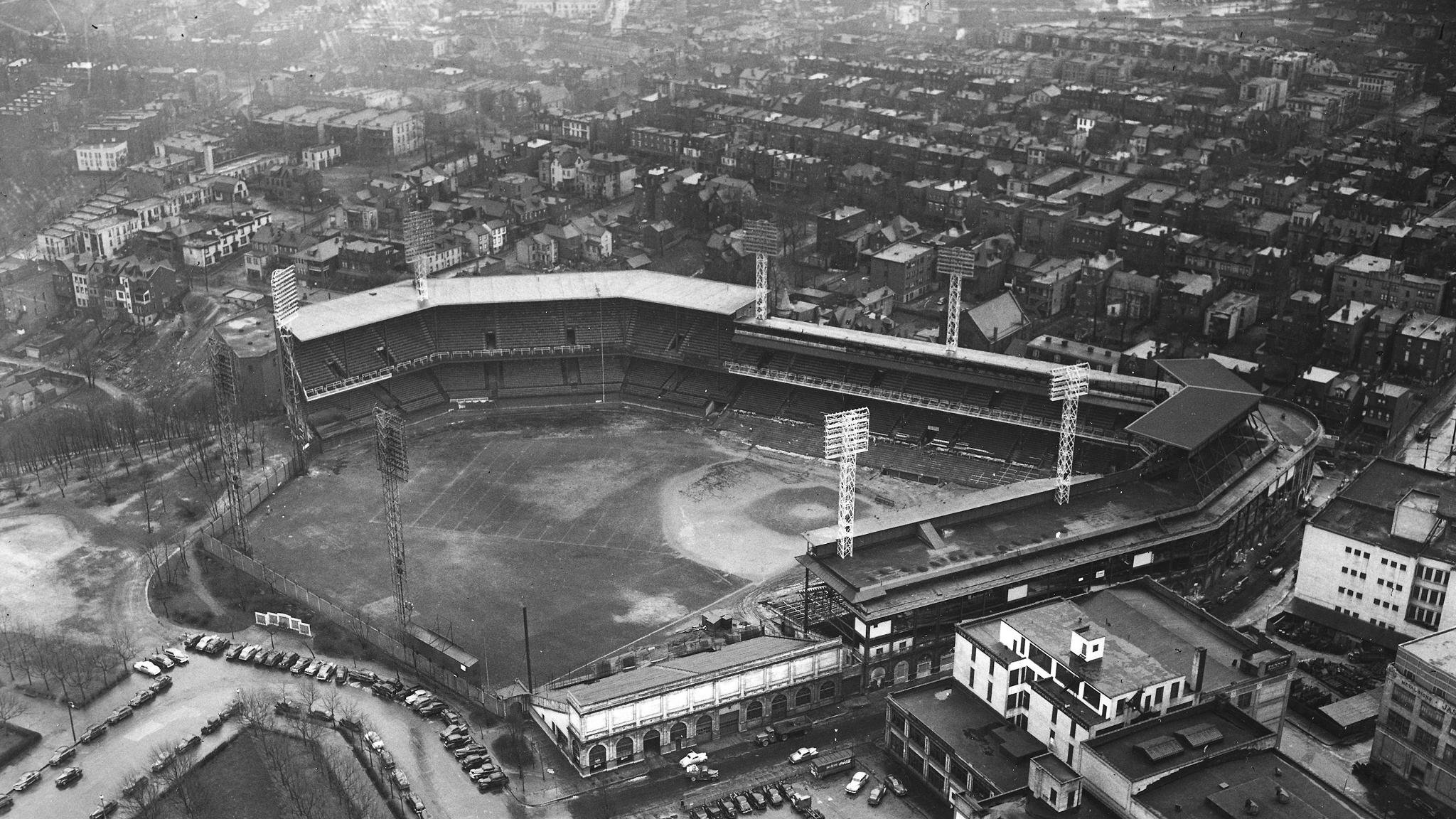

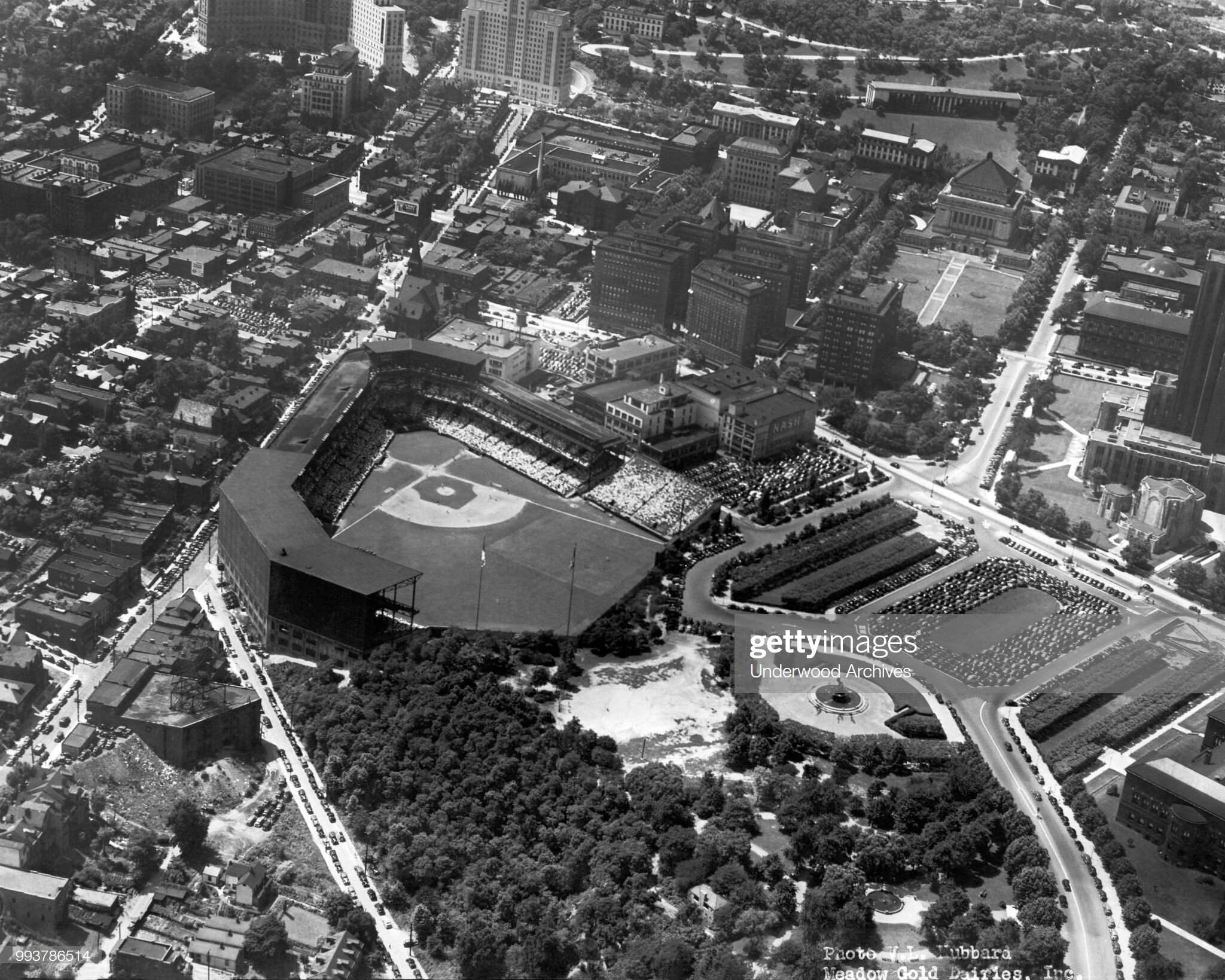

Dreyfuss’s decision to move the Pirates to Oakland resulted in a ballpark that would define an entire era of baseball and lift the sport to the level of a civic institution it remains at today. Early ballparks were often located on peripheral neighborhoods where land was cheap, allowing owners to buy up a large number of lots for a minimal price. Moving to Schenley Park saw the Pirates integrating into an established upper middle class neighborhood with natural views unlike any other park [4]. While not the first concrete and steel ballpark, coming just months after Shibe Park in Philadelphia, Dreyfuss built Forbes Field as the most innovative park up to that time with an aim to integrate it into the cultural center around him. Forbes Field’s exterior was built to complement the museums and library nearby, with arches and pillars producing a grand presence, reflecting the City Beautiful movement’s emphasis on architectural beauty as a way to improve urban conditions. Author Robert Trumpbour puts it as such, “Forbes Field was intentionally designed to be more upscale, with the hope that such a plan would not only attract the affluent, but the multitude of average citizens clinging to dreams of becoming rich [7].” Underground parking for automobiles, telephones, women’s bathrooms, and laundry machines to wash uniforms were just some of the unique touches of this modern stadium, which was to be expected in one of the most progressive cities in the country. Electric lights were also installed with the hopes of conducting night games in the future [7]. Even with these modern touches, many originally labeled this move as “Dreyfuss’s Folly,” due to the distance from downtown. It would be quickly proven that the ten minute trolley ride was no obstacle for fans [4]. Business leaders and working class citizens both flocked to the park, each seeing the game as a representation of their worlds and values. Business leaders saw baseball as a real time example of managerial hierarchy working towards a common goal. Meanwhile, workers saw baseball as exemplifying the importance of an individual’s craft [7]. With such a robust fanbase and a home at the cultural heart of the city, the team began to be seen as part of Pittsburgh. One newspaper covering the Pirates would proclaim, “Nothing advertises a city like a good baseball team [7].”

Pittsburgh’s civic pride was on an upswing internally, but external forces continually brought the economic fortunes of the city into question. In 1930, Harper’s Magazine published an article titled, “Is Pittsburgh Civilized?”, followed by a 1938 article in Forum titled, “Pittsburgh: What a City Shouldn’t Be [10].” The Pittsburgh Survey, a sociological look at the city in the first few decades of the Twentieth Century, concluded that, “never before has a great community applied what it had so meagerly to the rational purposes of human life [6].” Pittsburgh’s reputation relied heavily upon the steel industry which continually went through boom-and-bust cycles. Steel production plummeted during the 1930s, resulting in one-third of Pittsburgh residents being unemployed. Changes were needed and the corporate leaders of the city were first to act. In 1939, the Allegheny Conference on Community Development (ACCD) was founded by Richard King Mellon, heir to the Mellon banking fortune, and 24 top business leaders of the region, with the express aim of modernizing Pittsburgh. Howard Heinz, owner of the Heinz Corporation and member of ACCD, met Robert Moses at the 1939 New York World’s Fair and invited him back to the city to develop a plan to modernize the arterial roadways of the region. His final plan called for major boulevards to cut across the Lower Hill neighborhood, which was predominantly African-American. He described the neighborhood as a, “… slum that is no credit to Pittsburgh, and which has a depressing effect on available surrounding property [6].” Before the board could act on any recommendations World War II sparked the Pittsburgh economy, throwing the city into overdrive. The demand for steel put all revitalization plans on the back burner for the time being, but they would resurface before the war was over.

Composite of Planned Lower Hill Developments - 1965

Source: Carnegie Mellon University

More than a year before World War II would end, Pittsburgh leaders would be shaping what would become known as the Pittsburgh Renaissance. A 1944 article by the Wall Street Journal would rate Pittsburgh as a “Class D” city, signaling a bleak economic future. During this time period, downtown real estate values were dropping by over $10 million per year [11]. Two years later, the business community had a response. The 75th anniversary for the Kaufman’s department store was celebrated with a Pittsburgh in Progress exhibition that laid the groundwork for the Pittsburgh Renaissance, emphasizing solutions to the pollution crisis and addressing the fear that the city would lose its industrial base. ACCD followed up with their report, Pittsburgh: Challenge and Response, which argued the city needed large scale development and radical thinking, comparing it to the founding of the country nearly two centuries before [6]. While some of these civic plans would be spearheaded by the city, many more were privately funded and built. R.K. Mellon worked closely with Mayor Lawrence in order to achieve many of the initial goals, including reductions in air pollution and flooding issues. Mellon, as the largest stakeholder in the worst offending corporations, threatened to pull financial support from local companies that did not comply with the new mandates [10]. At the same time, ACCD returned to the plans laid out by Robert Moses, including the possibility of a multi-use sports stadium in the Lower Hill neighborhood. This plan was quickly removed from consideration after evaluating the sheer cost of relocating thousands residents. In its place, the 18,000 seat Civic Auditorium was built. While originally garnering favor among residents due to promises of expanded affordable housing in the neighborhood, support waned when those promises were not kept [6]. Over 8,000 residents were relocated along with the demolition of 1,300 buildings and 413 businesses [10]. ACCD also looked to lure corporations to Pittsburgh. Equitable Life Insurance Society, out of New York, agreed to relocate to Pittsburgh as part of its revitalization efforts. Eleven buildings were initially promised around The Point, the tip of downtown where three rivers converge, but only three would be built due to low occupancy rates. Equitable would describe Pittsburgh as a city who’s “appetite exceeds its digestion [10].” This desire to be a bigger city would factor into the fear of losing the Pirates as the landscape of baseball shifted while the Renaissance was in full swing.

As suburban growth accelerated and westward expansion continued, Major League Baseball began to see a shake up take place that would rattle cities who have grown to see their baseball teams as permanent fixtures in their community. Five teams would leave their home cities to expand westward [5]. At the same time, the league began expanding in 1960 to accommodate more teams and to put pressure on older teams to improve their ballpark facilities [12]. Sunbelt cities were actively pursuing existing franchises, promising larger stadiums built with public funding. New York, having lost two of its three teams, also began exploring attracting the Cincinnati Reds along with the Pirates, until they were awarded a new franchise with the Mets in 1962 [11]. A general feeling settled in for legacy cities, best summed up by author Aaron Cowan, that the, “…loss of a professional sports franchise amounted to a tacit admission that a city was dying [11].”

Not only were the Pirates, and Pittsburgh as a whole, fighting the demographic shift to the south and west, but also how progress was being defined in the Oakland neighborhood. In 1958, the University of Pittsburgh purchased the land beneath Forbes Field and began renting the ballpark to the Pirates. Their initial agreement for four years would eventually grow into twelve as the Pirates struggled to find a new home [5]. As the Renaissance kicked into high gear, the University took a leading role as it looked to establish itself as a national leader in emerging technologies. With limited developable land in Oakland, Forbes Field offered the best opportunity to expand [11]. The original plan for Forbes Field included converting the ballpark into affordable housing or into a mix-use pavilion, but the ballpark would come down in the end to make room for dormitories. The University also sought to create a research park, named Panther Hollow, that would be also be used by Carnegie Mellon University, formerly Carnegie Tech, but it would never be built. Oakland would continue to see itself grow as the educational and cultural hub of the city, with expansions to art museums and the construction of the WQED PBS station, where “Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood” would be filmed [6]. This left the Pirates with few choices moving forward.

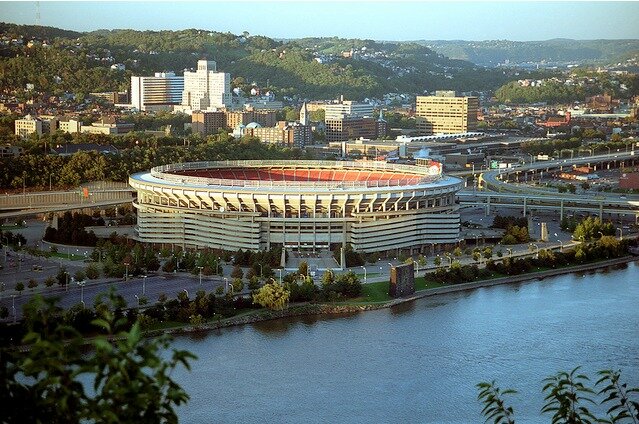

Talks of a multi-purpose sports stadium in Pittsburgh had been around since the 1950s as a way to maintain the presence of baseball and football within the city and attract newly suburbanized families back to the city. As part of the early stages of the Pittsburgh Renaissance a tract of land on the Northside just across the Allegheny River from downtown was eyed as a potential site for the stadium. As the 1960s rolled on this site became increasingly likely for a new stadium. Before construction could begin, the 84 acre site was cleared [6]. Old warehouses and defunct railroad tracks were removed, along with the relocation of 63 residents. Clearance was paid for by $14 million in federal urban renewal funds along with $5.5 million from both the city and county. Three Rivers Stadium, as it would be known, would be paid for through $40 million in 40 year city bonds, along with a 40 year lease agreement with both the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Pittsburgh Steelers [11]. An original design for the stadium called for a horseshoe design opening up to the downtown skyline [6]. After estimates came back $12 million over budget, the city opted for an enclosed oval that was easier to engineer. By closing the circle the stadium would act as a barrier between the fans and the city, creating a controlled space within the urban core that many at the time saw as desirable [11]. Suburbanites envisioned the city as a dangerous place, leading the team owners and city officials to pursue a stadium that would reduce any amount of time these visitors would need to spend in the urban core. A key aspect of this design was direct connections to the highway that would lead into the parking lots that surrounded the stadium. Although pedestrian connections were originally considered, they were never implemented as part of the project [11]. The end result was a stadium devoid of any personality or connection to the city, essentially creating a suburban friendly space within the urban environment at the expense of city residents.

Three Rivers Stadium opened 1970 near the end of the Pittsburgh Renaissance and remained one of the most visible failures of the time period. While downtown Pittsburgh and the Oakland neighborhood saw rejuvenation and life brought back to them, the neighborhoods just outside of downtown saw a mixed response. Over 3,700 buildings were razed, displacing over 1,500 businesses. The Point was transformed into a popular state park. Over 22,000 jobs relocated to newly built office towers around the Point after the $118 million project was completed, only $600,000 of which were public funds [10]. The national press heralded the Pittsburgh Renaissance as a success, often showcasing glamor shots of the gleaming new buildings, many of which showcased new construction techniques. They often overlooked many of the nuances in how the community perceived these changes. The Pittsburgh Courier, a prominent local newspaper in the African-American community, originally championed many of the changes, including the efforts in the Lower Hill neighborhood. The praise quickly changed to critique and outrage as promises continued to fall through on creating affordable housing as part of these efforts [6]. Jane Jacobs famously critiqued the city’s efforts as erasing chaos and character to replace it with monotony [6]. While only a small piece of the urban renewal effort in Pittsburgh, the sameness and monotony of Three Rivers Stadium would often be critiqued, even by players. Richie Hebner, a former third basemen for the Pirates, once remarked, “I stand at the plate in Philadelphia and I don’t honestly know whether I’m in Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, St. Louis or Philly. They all look alike [11].”

A monumental shift in ballpark design would soon coincide with a shift in the collective perception of cities. The SkyDome in Toronto, completed in 1989, would mark the end of an era defined by “futuristic” concrete coliseums and domes. As the era ended, a new one quietly began in Buffalo, New York where a ballpark with a more classic feel would be introduced in 1988. Pilot Field sat within the downtown Buffalo grid instead of surrounding itself with parking lots. Arches along the outside mimicked the iron work of classic ballparks and the size of the park fit its space within the neighborhood. While the attempt to draw a Major League team to the city failed, the groundbreaking nature of the ballpark would inspire a new era of planning [4]. At the same time Buffalo was attempting to attract a team, Baltimore was looking to save their own. In 1984 the Baltimore Colts fled to Indianapolis when a promised multi-use sports stadium continually fell through. Edward Bennett Williams, the owner of the Baltimore Orioles, leveraged the fear of losing both professional franchises to pressure the state into supporting a new stadium. Having grown up in Pittsburgh, Williams understood the failures of the Three Rivers Stadium design compared to the successes of Forbes Field. He forced the state to abandon the idea of a multi-use stadium, which they hoped would attract a new football team, in favor of a baseball specific facility in the heart of the city. Camden Yards, located on an old rail bed, would soon become the new standard the ballparks were measured against [4]. Baseball teams were looking to return to their urban roots and reintegrate into the urban fabric. The idea that a new neighborhood ballpark could become part of the life of a city again, where, “…even persons who were not rich could live well,” instead of the newly outdated notion of safety within suburbia [13]. Essentially, the movement back to the city would allow the game to grow its fan base and support within the region. Although the planning in this era of ballparks was a vast improvement over the last, it would be marked by these forms of pressure campaigns seen in Baltimore. Congress understood the pressures that cities were under to provide stadiums for their professional sports teams and hoped to curb that pressure in 1986. By closing a tax exemption, Congress capped a city’s ability to use revenues and lease payments to pay back tax-free bonds for stadiums at less than 10 percent, which would mean a city would need to raise taxes to pay for 90 percent of the cost. The assumption was that cities would never agree to such terms [14]. With another expansion to the Major Leagues in 1990, a building boom driven by municipal financing soon followed. Over the course of the next twenty years, the average stadium age would drop from 31.8 years to 20.9 years, signaling a willingness of cities, including Pittsburgh, to fund these large scale projects [12].

After the flurry of development during the Pittsburgh Renaissance, the city found itself looking to embrace its new, smaller size and stitch back together the neighborhoods that made it unique. By the early 1990s, the failures of Three Rivers Stadium were evident. Residents and fans often complained about the lack of accessibility, even though its highway connections were meant to make accessibility its main selling point to the suburban crowds. In between the 1991 and 1992 seasons, Mayor Sophie Masloff announced a plan to build a new baseball specific park, just twenty years after Three Rivers had opened its doors. This was all but an admission that the plans of the past had failed to address the needs of the city and its teams [5]. It was also an admission of the reality of Major League Baseball. The Pirates, as part of their 1996 sale, were required by the league to build a new ballpark or risk having the franchise moved [4]. Pittsburgh had seen its urban population drop from over 677,000 in 1950 to just over 300,000, while maintaining a stagnant metropolitan population of around 2.4 million [15]. Other cities had been growing quickly and were angling to land a major league team to cement their new status. The Pirates and Steelers were both in positions to be lost, prompting the city to act. The State of Pennsylvania granted the Pittsburgh region permission to vote on a tax increase to fund two stadiums, which would be built in the parking lots of Three Rivers. The vote failed spectacularly, with over 68 percent of residents voting it down, including 58 percent of city residents [16]. Residents were not willing to spend public funds on these stadiums, yet they also overwhelmingly acknowledged viewing these teams as integral to the civic pride of the city [16]. Pushing forward with plans to preserve Pittsburgh’s status as a major league city, the Allegheny Regional Asset District (RAD) agreed to put up $13 million per year to pay off the bonds for Three Rivers Stadium as well as the demolition costs. The Pirates and the Steelers both agreed to putting up the funds for a significant portion of the development, along with attracting local business leaders to invest. By 1999, the State of Pennsylvania approved additional funding for both stadiums in Pittsburgh, along with two stadiums in Philadelphia [16]. While Three Rivers Stadium seemed desolate and separated from the city, PNC Park would become an integral part of its surroundings. Building off city planning efforts from the 1980s and 1990s, the ballpark would include park space along the riverfront and pedestrian access on all sides. The Roberto Clemente Bridge, named after one of the Pirates’ most famous players, is often converted into a pedestrian only bridge directly connecting downtown Pittsburgh with PNC Park, similar to how original plans for Three Rivers had envisioned. Built with a capacity of around 38,000, the ballpark is one of the smallest parks in use today. The smaller capacity allowed the stadium to be built with two decks instead of three, creating a smaller profile more reminiscent of Forbes Field, and fitting with the Northside neighborhood it resides within. Architectural references to the city around it, including the use of Kasota stone and exposed steel, give the ballpark a feel of civic importance and unity that was lost with the concrete of Three Rivers [4]. PNC Park quickly became considered one of the greatest ballparks in baseball and a true asset for the city. In 2003, Jim Caple of ESPN remarked, “Ray Kinsella [Field of Dreams] was wrong. Baseball heaven isn’t in Iowa. It’s in Pittsburgh, along the banks of the Allegheny River [4].”

Baseball was not the only aspect of civic life being rewoven into the urban fabric of Pittsburgh. The Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, beginning in 1984, has worked to reimagine a number of old theaters located in the old Red Light District. Directly across the river from PNC Park, the Cultural District has grown to include theaters for the Pittsburgh Symphony and Opera, modern dance groups, Broadway musicals, and more avant garde productions. Benefitting from many of the philanthropic organizations that have sustained cultural touchstones throughout the city, the Cultural District has been able to diversify its offerings to an extent many similar size cities are unable to [17]. Outside of the Cultural District, old mill sites have been transformed into retail and design centers, as well as museums. The Pittsburgh Technology Center converted an industrial site from 1849 into a tech research center where Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh have teamed up. And adjacent to the newly built stadiums resides the largest art museum dedicated to a single artist in the country, the Andy Warhol Museum [18]. Art, technology, and sports have woven themselves into Pittsburgh, much in the same way they once had over a century ago, creating links to the neighborhoods and history around them.

Roberto Clemente

Source: Zinn Education Program

Even with this new focus on neighborhood planning and urban development, these institutions’ physical presence alone does not help correct the issues of the city’s past. Currently over 13 percent of Allegheny County residents live below the poverty line, with one-third living near it. Communities of color, single-parent households, and youth are often the most impacted [19]. The large philanthropic interests of the city’s corporate leaders have looked to address many of these lingering issues that have resulted from past urban planning efforts. The Pittsburgh Pirates have begun a multitude of charities, nestled under the banner of Pirates Charities, that focus on childhood well being, nutrition, and physical health [20]. The Roberto Clemente Foundation, run by the family of the former Pirates player, has focused on addressing long-term poverty and aid for natural disaster recovery, primarily within Pittsburgh and Caribbean nations. The team and these organizations, as of late, have adopted a stance best summed up by Roberto Clemente: “If you have an opportunity to accomplish something that will make things better for someone coming behind you, and you don’t do that, you are wasting your time on this earth [21].”

Pittsburgh’s evolution from industrial powerhouse through deindustrialization and suburbanization to a progressive mid-size city today has been showcased on a national stage through the ballparks of the Pittsburgh Pirates. Forbes Field showcased the modernization and civic minded nature of the early Twentieth Century. Three Rivers Stadium looked to create a controlled space within the urban center to appeal to suburbanites fleeing the city. And PNC Park embraced a smaller scale city that wanted to balance its past with the future, which includes making amends for the past and current injustices experienced by the community it seeks to be a part of. Baseball may not be the perfect analogy for America, but the ballparks that house the teams continue to represent the duality of American desires; rural pastures and industrial might.

[1] Patricia J. Finney. “Landscape Architecture and the ‘Rural’ Cemetery Movement.” Center for Research Libraries. https://www.crl.edu/focus/article/8246

[2] Bender, Thomas. “The ‘Rural’ Cemetery Movement: Urban Travail and the Appeal of Nature.” The New England Quarterly (June 1974): 196-211 https://blogs.stockton.edu/nature/files/2011/09/Bender-The-Rural-Cemetery-Movement.pdf

[3] Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. “1833-1875: Rural Cemetery Movement.” Accessed October 5, 2019. http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/portal/communities/cemetery-preservation/development/1833-1875.html

[4] Goldberger, Paul. Ballpark: Baseball in the American City. New York. Alfred A. Knopf, 2019.

[5] Bonk, Daniel L. “Ballpark Figures: The Story of Forbes Field.” Pittsburgh History (Summer 1993), 52-70

[6] Grimley, Chris, Kubo, Michael, Samahy, Rami el. Imagining the Modern: Architecture and Urbanism of the Pittsburgh Renaissance. Pittsburgh. The Monacelli Press, 2019.

[7] Tumpbour, Robert. “Forbes Field and the Progressive Era.” In Forbes Field: Essays and Memories of the Pirates' Historic Ballpark, 1909-1971. Edited by David Cicotello and Angelo J. Louisa, 25-35. McFarland and Company, Incorporated Publishers, 2007.

[8] Byrnes, Mark. “What Pittsburgh Looked Like When It Decided It Had A Pollution Problem.” City Lab. June 5, 2012. https://www.citylab.com/design/2012/06/what-pittsburgh-looked-when-it-decided-it-had-pollution-problem/2185/

[9] Dietrich II, William S.. “Andrew Carnegie: The Black and the White.” Pittsburgh Quarterly , Summer 2007 https://pittsburghquarterly.com/pq-people-opinion/pq-history/item/359-andrew-carnegie-black-white.html

[10] Fitzpatrick, Dan. “The Story of Urban Renewal.” The Post-Gazette , May 21, 2000. http://old.post-gazette.com/businessnews/20000521eastliberty1.asp

[11] Cowan, Aaron. “A Whole New Ball Game: Sports Stadiums and Urban Renewal in Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis, 1950-1970.” Ohio Valley History, Fall 2005. http://library.cincymuseum.org/topics/b/files/baseball/ovh-v05-n3-who-063.pdf

[12] J-Doug. “Stadium Boom Amounts to Fountain of Youth for MLB Parks.” SB Nation. January 4, 2011. https://www.beyondtheboxscore.com/2011/1/4/1912546/stadium-boom-amounts-to-fountain-of-y outh-for-mlb-parks

[13] Bess, Philip. “The Grace of Neighborhood Ballparks: The Guidelines for Urban Baseball After the Era of Cheap Petroleum.” 2008 Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University: 28-39. https://www.baylor.edu/content/services/document.php/75225.pdf

[14] Paulas, Rick. “Sports Stadiums Are a Bad Deal for Cities.” The Atlantic. November 21, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/11/sports-stadiums-can-be-bad-cities/5763 34/

[15] Benfield, Ken. “Where Pittsburgh Has the Sunbelt Beat.” City Lab. February 2, 2012. https://www.citylab.com/life/2012/02/where-pittsburgh-has-sun-belt-beat/1158/

[16] Groothuis, Peter A., Johnson, Bruce K., Whitehead, John C.. “Public Funding of Professional Sports Stadiums: Public Choice or Civic Pride.” Eastern Economic Journal vol. 30, no. 4, Fall 2004: 515-526

[17] Tierney, John. “How the Arts Drove Pittsburgh’s Revitalization.” The Atlantic. December 11, 2014. https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/12/how-the-cultural-arts-drove-pittsburghs-re vitalization/383627/

[18] Smith, Caitlin. “Pittsburgh, City of Renewal.” The Atlantic . September 2009. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/09/pittsburgh-city-of-renewal/307700/

[19] Pittsburgh Foundation, The. “Poverty In Our Region.” Accessed October 5, 2019 https://pittsburghfoundation.org/poverty-in-region

[20] Major League Baseball. “Pirates Charities,” Pittsburgh Pirates. Accessed November 25, 2019. https://www.mlb.com/pirates/community/pirates-charities

[21] Roberto Clemente Foundation“Roberto Clemente Foundation Community Outreach,” Accessed November 25, 2019. https://robertoclementefoundation.com/community-outreach-2/